Argentina has many natural resources, that is a given. However this is not enough: we also need to develop capabilities, spaces, relationships amongst stakeholders, financing, etc. Bioeconomy can be a way to do this and Rosario can be an example for the rest of the country. How? This study on Rosario’s biocluster offers some key points to think about how to scale this strategy to other regions.

Illustration: Nestor Agustín Vassallo

A subnational bioeconomy strategy can help bridge productivity gaps and promote the repurposing of primary sectors towards knowledge-intensive activities. This paper explores the potential of this development strategy focusing on the Rosario biocluster case, specifically on firms using biotechnology to address agricultural challenges, such as reducing the use of agrochemicals or replacing them with biological products, enhancing the efficiency in producing biofuel or crop tolerance to droughts. And it further dives into the challenges of institutionalizing and expanding this strategy to other regions of the country.

Bioeconomy as a national development strategy

The growing demand for biological products to replace those based on fossil fuels and boost agricultural productivity while minimizing environmental damage represents an opportunity for our country.

Against this backdrop, the bioeconomy is a key strategy. It is a sustainable development paradigm, consisting of the use and transformation of resources of biological origin to produce goods and services, through the intensive use of scientific and technological knowledge.

Expanding the bioeconomy could contribute to the modernization of traditional activities (through the adoption of technologies such as green chemistry, modern biotechnology or nanotechnology) while generating spillovers to other sectors of the economy.

Our country has the capabilities required for such a strategy, namely, a diversity of natural resources throughout the territory; dynamic agro-industrial chains craving innovation; a public science and technology system known for its quality; and a set of public instruments designed to foster knowledge-based activities.

The debate on the most appropriate instruments to promote the bioeconomy has shifted in recent years from the national to the subnational level, prioritizing the implementation of policies aimed at supporting bioregions. Bioclusters (or bioregions) are promoted through a geographical organization of the territory based on bioeconomic potential, allowing a territorial approach that articulates the biomass offering of each geographical unit (microfauna, soils, climates and genetic varieties) with the capabilities available to exploit such potential.

Bioregions as a subnational promotion strategy

A strategy aimed at promoting bioeconomy is particularly relevant in a federal country like Argentina, with a great diversity of biological resources spread over a vast territory. The implementation of a regional approach for the promotion of the bioeconomy can help reduce sectoral productivity gaps and reduce inequality among regions.

However, this subnational approach has not yet been translated into a bioregional development plan. And the debate has not moved beyond academic research, the production of policy-making inputs and, at best, a few isolated policies.

There are remarkable —despite still incipient— examples of biocluster development in the country, which point to the potential effect of this production strategy in reducing interregional productivity gaps.

A case of growing interest is the agro-biotechnology cluster in the Rosario-Santa Fe corridor. The region has embarked on a process of productive diversification through the emergence and consolidation of biotechnology firms with export capacity that compete at the forefront of the global technological frontier leveraging the biomass and industrial capabilities available which adds to its sound network of science and technology institutions.

Case study: the Rosario-Santa Fe agro-biotechnology cluster

Despite being an essential condition, the wide availability of agricultural biomass alone cannot account for the emergence and strengthening of the Rosario-Santa Fe biocluster. Analyzing and understanding these other factors is key, as it can provide input for the development of a bioeconomy strategy in other regions and help identify the capabilities required for the emergence and consolidation of bioeconomic activities at the regional level, as well as the challenges that may hinder their consolidation.

To better understand the emergence of this cluster, we will use an analytical framework that proposes six factors or capabilities that must be present in each region to promote transformative activities aimed at modernizing production processes, incorporating knowledge and creating value.

What are the factors that fuel the development of bioregions? | Biomass endowment Biomass endowment (water, air, soil, forests, water resources, local food, etc.) or the existence of one or more strong primary sectors (agriculture, fisheries, forestry, etc.). |

Industrial and business capabilities Large companies, SMEs and start-ups needed to scale-up technological development, business capabilities to bring products to market (business and regulatory expertise) and availability of skilled labor. | |

Scientific and technological capabilities Availability of qualified human resources (leading scientists), research center and R+D infrastructure. | |

Business and entrepreneurial culture Promoting stakeholders’ sense of belonging to a cluster and the existence of formal and informal collaboration networks. | |

Financing availability Access to a variety of financing alternatives, including seed and venture capital, public funds, banking and non-banking loans. | |

Support institutions and networks Formal and informal organizations designing and organizing cluster operations, including the existence of technology transfer agencies and incubators, infrastructure to support innovation activities and public policy regulations and incentives. |

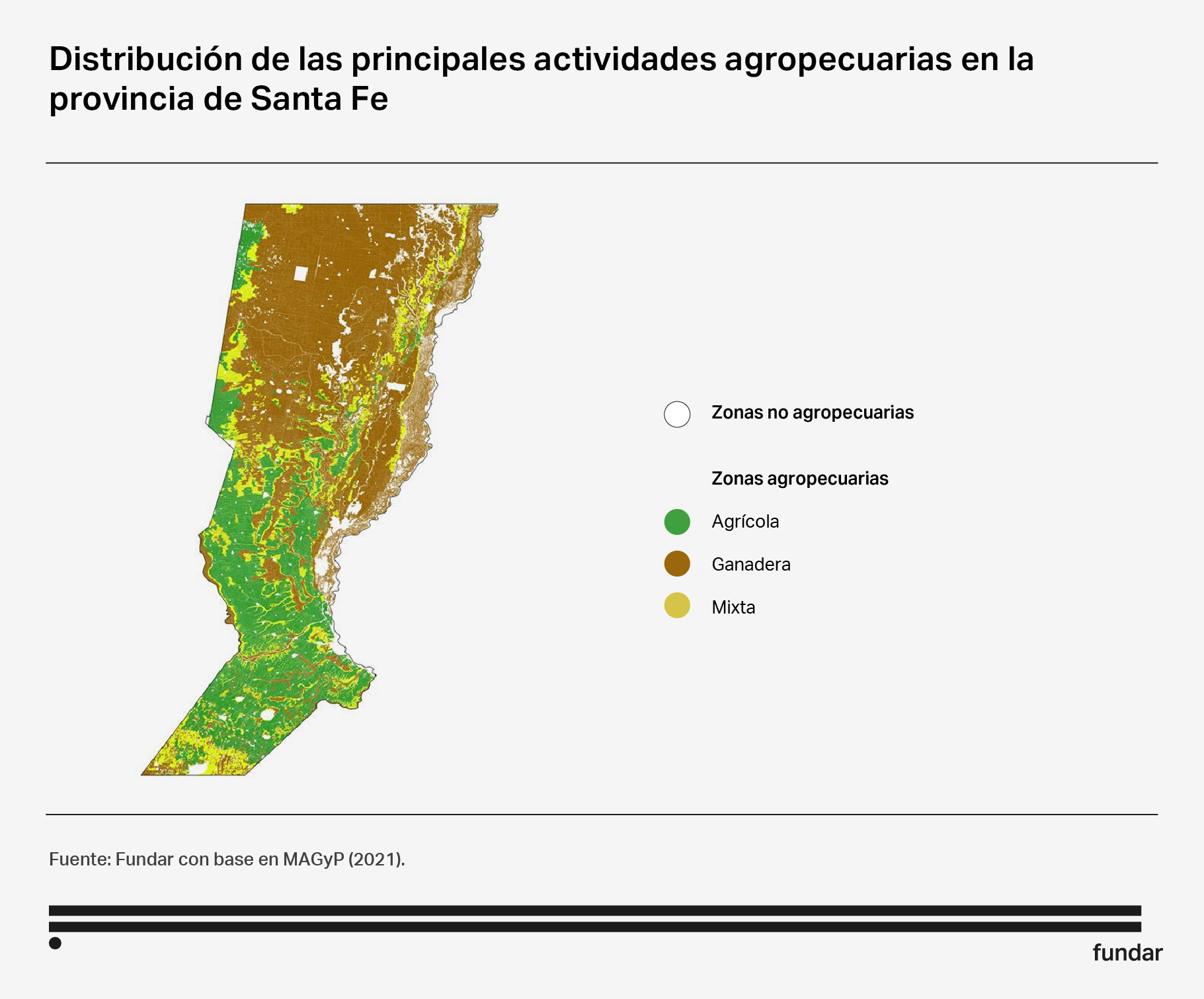

Biomass endowment

Rosario is located in one of the most important agricultural regions of the country. Santa Fe’s agricultural sector accounts for 16.8% of the value added generated by the sector at the national level and 17.5% of the province’s gross geographic product. The southern departments of Santa Fe, including Rosario, also have the largest share of arable land and agricultural production in the province.

This has made Rosario an attractive location for the establishment of input and seed supply chains, which in turn has paved the way for biotechnology specialization with a focus on agriculture.

Industrial and business capabilities

Rosario is also one of Argentina’s most important industrial clusters, along with Córdoba and Greater Buenos Aires. The region concentrates a wide array of productive and business capabilities linked to agribusiness, which boosted the development of the cluster through a series of mechanisms:

- The specialization of production and the large suppliers established in the region have tilted the biocluster towards a specialization in agricultural biotechnology.

- The density of the production network contributed to developing strategic partnerships between established and emerging companies.

- The circulation of human resources skilled in corporate business and productive management facilitated the scaling up of scientific developments to a marketable product.

Scientific and technological capabilities

The Rosario Science and Technology Center and the Santa Fe Science and Technology Center, both under the umbrella of CONICET, concentrate the province’s biotechnology capabilities.

The formulation and strategic execution of science and technology policies, coupled with substantial public investment in capacity building, have proven instrumental in shaping the requisite conditions for the emergence of the biocluster. This strategic endeavor has produced a critical mass of skilled human resources, serving not only to propel advancements in fundamental scientific research that underpins innovative product development but also facilitating the integration of highly qualified scientists in the TBEs set up in recent years.

Financing availability

While public investment is critical in supporting basic science and human resources, and even in the early stages of projects, private financing has been critical in supporting the testing, deregulation, and industrial scaling of developments.

Private capital played a key role in the financing of emerging companies. This result was favored by the fact that both individual and corporate investors were already operating in the agribusiness sector and were in a better position to evaluate the business opportunity and/or capitalize on this development in their own productive process.

Also worthy of note is the role played by accelerators, incubators and venture capital funds, known for investing in early-stage business projects and their appetite for developing disruptive products with great business potential.

Support institutions and networks

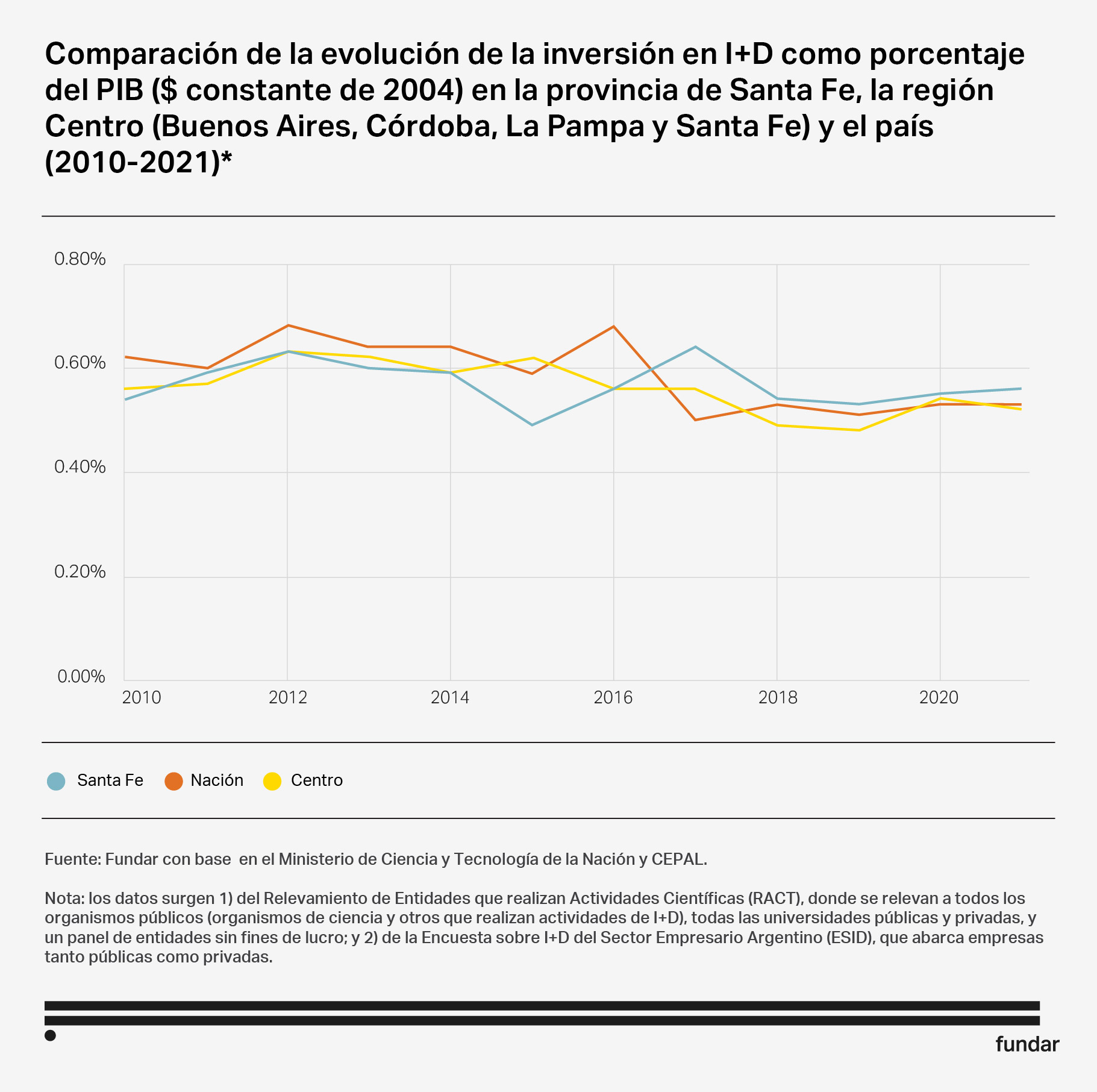

Biotechnology support policies have played a key role in fostering the dynamic growth of the province’s biotech business ecosystem. Over the decade spanning from 2008 to 2018, Santa Fe consistently averaged an annual R&D investment of 0.7% of the region’s GGP. While still short of the 1% target set by the national scientific and technological system, the province maintained a commendable record, consistently outperforming the national average by 0.1 percentage points throughout the period.

Santa Fe stands out among its counterparts with a distinctive track record in the implementation of science, technology, and innovation policies. In particular, there is a strong emphasis on applied research, innovation, and the cultivation of techno-productive capacities tailored to the specific needs of the provincial landscape.

In terms of provincial policy, a key factor contributing to this success has been the unwavering political commitment to supporting and nurturing the biotechnology cluster through successive administrations and despite political changes in government.

The support of this political initiative is also underpinned by a dense network of informal relations between government officials, scientists and business people participating in the cluster at both the provincial and local levels, which facilitates the exchange of information and joint diagnosis.

Challenges for expansion beyond Rosario-Santa Fe

How can these processes be institutionalized? How can they become more predictable and how can they be scaled up to other regions in the country? After having described the achievements and potential of the Rosario biocluster and the conditions that have favored this evolution, this paper proposes public policy guidelines to address some of the challenges identified, focusing on the process of articulation between the public innovation system and the productive sector.

Challenge 1: Ensuring continuity of public policies

The availability of skilled human resources is a growing concern among ecosystem stakeholders. In order to meet this challenge, it is necessary to secure and increase investments in science and technology, including not only the compensation of researchers and grant holders but also in infrastructure and inputs, across all institutions that are part of the system (CONICET, INTA and universities).

Challenge 2: Building and supporting bridges between the public and private sector

The second challenge is to strengthen the link between the institutions involved in the Science, Technology and Innovation Plan (CTI) and the private sector. To do this, it is necessary to work on multiple fronts. On the one hand, CTI institutions continue to be limited by the system’s overly academic approach, which rewards basic science and publications over technological and technology transfer activities. It is thus necessary to revise the incentives offered to grant holders and researchers, through a symbolic and effective recognition of technological and technology transfer activities.

It is also necessary to strengthen technological training (not only in basic science but also in science-based problem-solving), while encouraging the training of scientists and biotechnologists in topics critical for the development of ventures, including regulatory issues, intellectual property and the basics of business management.

Challenge 3: Institutionalizing and scaling up these processes

Some of the successful stories of the creation of technology-based companies (TBCs) are based on public-private articulation processes that often depend on contingent circumstances and founders’ idiosyncrasy, or on informal and personal relationships that compensate for the lack of more formal networking mechanisms. The challenge is how to institutionalize and scale up these processes.

University technology liaison offices need to be strengthened in order to generate economies of scale jointly with the productive sector and to promote joint work on the management of regulatory and patent issues.

In the same vein, it is desirable to develop policies favoring the provision of public goods in line with the common needs of startups, including plans for public-private investment in laboratories, testing centers, and regulatory and intellectual property capacity building.

Another important aspect of this challenge is the strengthening of accelerators and entrepreneurial capital, proposed as a possible tool to promote the collaboration between the S&T system and the productive sector.