The COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical tensions like the U.S.-China rivalry, and the war in Ukraine have reshaped trade, investment, and global economic integration. While the Global North sets the pace in this reconfiguration, nations in the Global South can seize the opportunity to foster development. Key to this endeavour is adopting a sharp, proactive approach to international trends, as illustrated by countries such as South Africa, Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico.

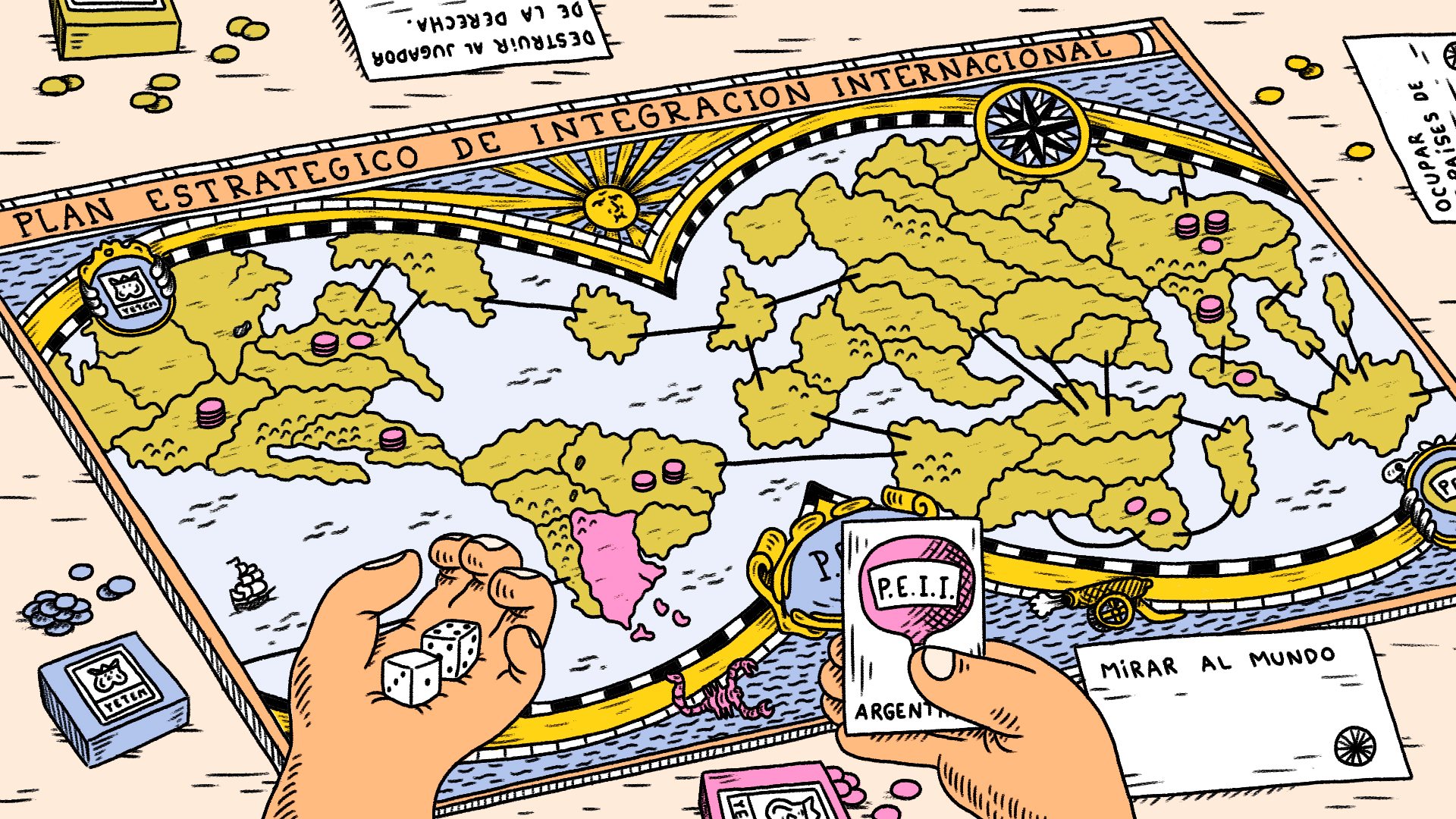

Illustration: Guido Ferro.

Global Reconfiguration and New Economic Policy Instrument

The international system changed radically after crises such as the 2008 financial crisis, the 2020 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. These events marked the end of hyperglobalisation and ushered in a phase of global reconfiguration, marked by geopolitical tensions, technological advances and climate challenges. This process does not imply a complete de-globalisation, but rather a profound change in the dynamics of economic interdependence that altered the rules of international integration and the role of states in global economies.

To describe this new scenario, we focus on four dimensions that explain the transition from hyper globalisation to the era of global reconfiguration:

- the transition of power in the international order,

- the type of instruments implemented,

- the prioritisation of strategic economic sectors,

- the geographical scope of production.

Power transition in the international order

The centre of the global economy shifted from one dominated by the United States to one with a greater diversity of actors, most notably the rise of China. This transformation reflects a more diffuse distribution of economic power. With its model of state capitalism, China challenges Western powers: it leads in key sectors such as technology and occupies a predominant role in trade in goods and foreign direct investment (FDI). Its leading role in international organisations and the creation of new economic institutions reinforce its global position.

The US responded to this with protectionist strategies and the reconfiguration of alliances, based mainly on geopolitical alignment. These practices were soon replicated in other countries of the Global North, thus changing the international landscape.

Type of instruments implemented

State intervention gained prominence in trade regulation and foreign direct investment, adopting a more politicised approach. Trade policies now pursue non-exclusively economic goals such as competitiveness in strategic sectors, climate change mitigation, and the resilience of value chains to prevent or recover from crises. Economic flows became subordinated to a logic of security and competition.

This shift is reflected in three main trends.

Strategic use of trade flows and increased protectionism

Since the 2008 financial crisis, trade-restrictive measures and controls on foreign investment have increased. Other unilateral actions such as production subsidies and incentives for reshoring (domestic relocation or repatriation of production) and friendshoring (geopolitical proximity) have also increased. These measures were driven by geopolitical factors, such as competition between China and the US, and are part of a “New Industrial Policy“.

The negotiation of new trade agreements and new instruments oriented by geopolitical affinity

Countries are signing more agreements, but they do so with a geopolitical focus and non-commercial goals. Mini-deals or memoranda of understanding, more flexible mechanisms focused on promoting resilience in strategic sectors such as critical minerals, have become popular. Cooperation and infrastructure investment programmes (aimed at promoting foreign investment) have also become vehicles for international competition.

The weakening of multilateralism and increase in unilateral actions

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) lost its capacity to regulate global trade, leading to increased unilateral actions with extraterritorial effects, further complicating trade relations.

New strategic economic sectors

Strategic sectors are not the same in the post-pandemic world as in hyperglobalisation. Whereas in previous years financial services and technological manufacturing stood out, today priority is given to sectors linked to:

- Energy transition (critical minerals such as lithium, copper and cobalt),

- Advanced technology (such as semiconductors, given their wide application in industry and defence),

- Economic security (given the increasing digitisation and growth of data-driven services).

The geographic scope of production: geo-economic fragmentation and slower pace of global growth

Since 2016, trade and investment as a whole have been growing more slowly than in the previous stage of hyperglobalisation, and are increasingly driven by ideological and geopolitical preferences. The concepts of reshoring (repatriation of production), nearshoring (regionalisation) and friendshoring (geopolitical alignment) reflect these changes.

However, this is not deglobalisation, but rather a global reconfiguration. The interconnectedness of the international economy remains strong. What is in dispute is control over value chains rather than the design of autarkic strategies.

Four cases of policies for the international insertion of the Global South

This new context calls for a rethinking of development policies and international insertion strategies that connect local markets with global ones and offer solutions to external risks. The economies of the North are leading the way in this reconfiguration. The countries of the Global South are not mere spectators: they can find opportunities to position themselves as relevant actors in these new global dynamics.

The cases of South Africa, Brazil, Indonesia and Mexico show how middle-income countries are adapting their strategies to respond to these challenges. Although approaches vary, they share three general strategies: i) strengthening national capacities, ii) diversifying risks, and iii) leveraging international agreements to build resilience and ensure local development.

Economic diplomacy as an engine for development

South Africa focuses its strategy on economic diplomacy, using international agreements and bilateral relations to drive its industrial policy. Its approach combines local capacity building with external risk diversification.

At the regional level, it prioritises the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), which seeks to expand its industrial base through higher value-added products, especially in manufacturing and critical minerals.

At the global level, it applies a multi-alignment, balancing relations with actors such as the US, China and the EU. It also relies on multilateral fora (such as the BRICS and the G20) to position itself as a leader of the Global South and to promote regulatory frameworks that protect the interests of emerging economies.

Reindustrialisation and sustainability at the core

Brazil identified an opportunity to define strategic sectors and advance new policy instruments. It adopted a reindustrialisation strategy linked to sustainability, focusing on agro-industry, the bioeconomy and energy transition. In turn, Brazil’s strategy combined economic and environmental diplomacy to legitimise the measures adopted internationally, taking advantage of the permissive spaces on the international stage.

Resource nationalism and diversification

Indonesia opted for a resource nationalism approach, restricting the export of raw materials (such as nickel) to encourage industrialisation. This strategy allowed the development of industries related to the manufacture of stainless steel and batteries for electric vehicles, key sectors in the global energy transition. The strategy was complemented by the promotion of investments in nickel processing industries and the pursuit of cooperation agreements on critical minerals. However, it led to increased external vulnerability due to its dependence on China.

🇲🇽 Mexico

Energy sovereignty and harnessing of TMEC

Mexico focused its strategy on energy sovereignty, strengthening domestic oil production and reducing dependence on external actors in the energy sector. Its policy included regulatory changes to restrict foreign direct investment in key areas (such as electricity generation) while seeking to guarantee state control over resource exploitation.

The permissiveness of global governance and the relative power that Mexico’s interdependence with the US generates opened up space for the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador to take these actions.

Understanding the changes of the global reconfiguration to improve our international insertion

These four experiences show that global reconfiguration can be an opportunity for developing countries that manage to adapt their policies to the new realities of trade, investment and international relations.

They leave us with four main lessons for thinking about Argentina’s insertion strategies.

Understanding the dynamics of global reconfiguration to identify opportunities and constraints in their international insertion

In order to develop a local strategy, the global picture must be known. Having an accurate diagnosis will help identify areas where Argentina can promote autonomous policies without facing retaliation, avoiding passive adaptation to a constantly changing international environment.

Enhancing state capacities to meet the challenges of global reconfiguration

This includes strengthening data management, modernising the regulatory framework and designing institutions to support industrial and trade policy. It is also key to consolidate a specialised bureaucracy and equip it with the tools to anticipate global trends and react quickly. An agile and strategic state can better negotiate international agreements, protect key sectors of the economy and foster competitiveness in a fragmented global system.

Prioritising strategic sectors and align productive policy and foreign policy with them

This selection should be aligned with energy transition and technological changes, taking advantage of opportunities arising from global demand for renewable energy and advanced technologies to increase economic resilience and reduce external vulnerability.

Diversifying international relations and seizing opportunities

Actively participate in multilateral fora, seek trade agreements that reflect the country’s needs and strengthen ties with strategic partners. Diplomacy should be a tool to maximise market access, protect key sectors and encourage investment in priority areas. Argentina must adopt a balanced approach that combines access to global markets with the protection of its economic sovereignty and development objectives.