Argentina could become an international brand in software, as it already is in other products. This will not happen automatically. The development of the new generation of software companies requires a public policy aimed at financing their latent potential. Measures aimed at reducing operating costs or increasing the availability of human resources are not enough. It is a matter of devising a new agenda that is more finely tuned to their needs and challenges. It implies, on the one hand, rethinking the current sectoral promotion regime for the future and, on the other hand, implementing packages of measures to complement it.

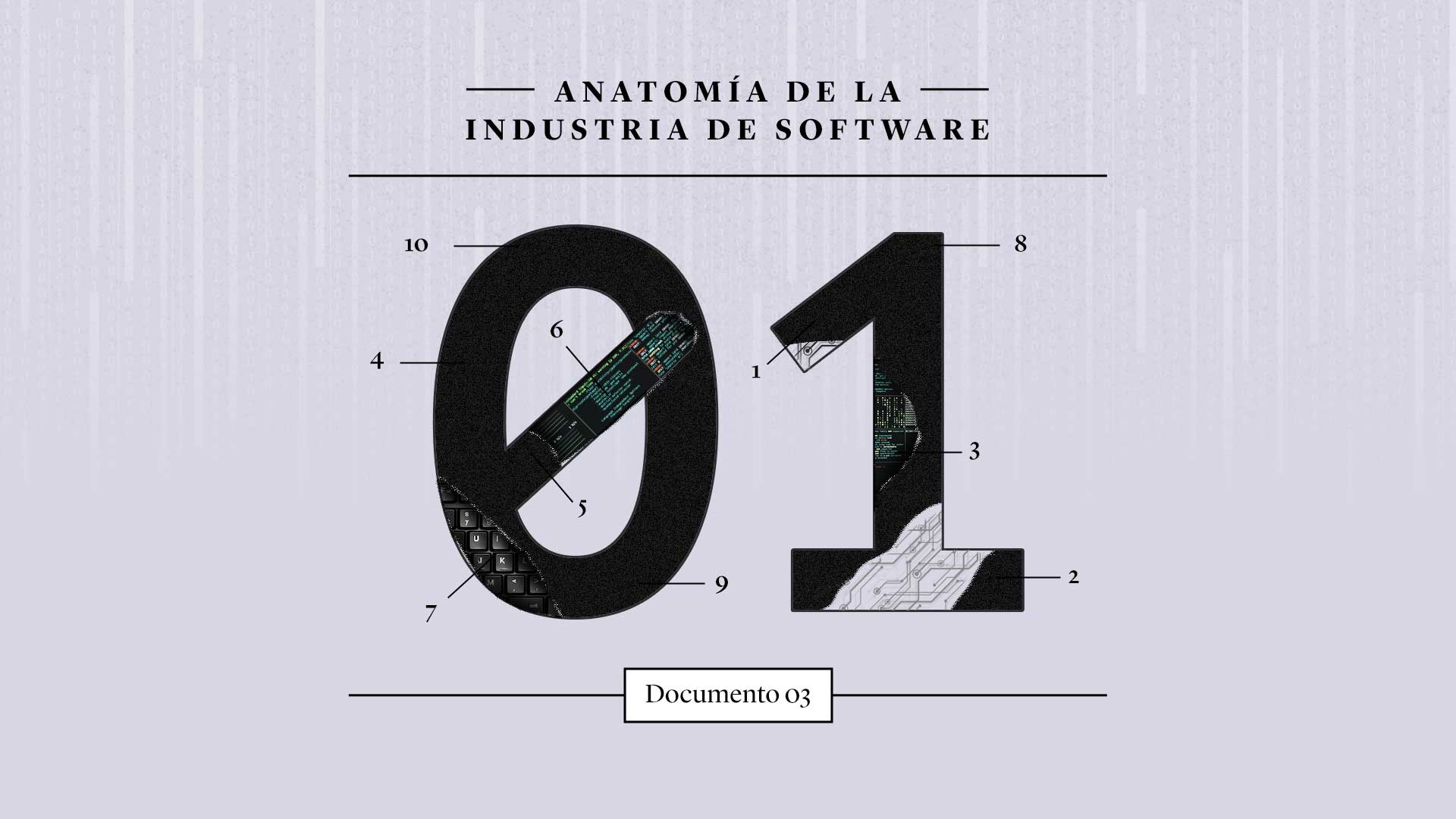

Illustration: Micaela Nanni.

A new map of ideas for thinking about the software industry

Argentina can now propose that a much larger universe of software and IT services companies can specialize and, thus, become internationally inserted in high value-added segments, boosting talent-intensive exports in the medium term.

The country has comparative advantages. More unicorns were born here than in other comparable middle-income countries. Developing a brand of “Software from Argentina” can help global market players understand that this unusual birth rate of leading companies is associated with aspects that distinguish our country from others in the Global South, and it would help start-ups win markets.

This requires a new map of ideas. Changing the framework with which we interpret what is happening today with the software industry in Argentina and what are the possible futures that open up from the potential it already has. This new guide, which must necessarily be built between private and public actors, will allow us to stop doing more of the same and implement an innovative agenda of sectorial policies.

Even if the current macroeconomic disarray and the country’s historical institutional and regulatory volatility reduce the probability of success of any public policy action, this is no reason to delay the design of a consistent public-private agenda for the software sector, the implementation of which could have an impact if the country were to achieve political and economic stability shortly.

Sectoral promotion regime

Many countries have tax schemes aimed at reducing operating costs, attracting investments and promoting the growth of the sector as an export platform. However, we must ask ourselves if the local regime is not -in the end a patch to palliate eventual distortions (exchange and tax, among others) that companies operating in Argentina face concerning their global competitors.

Twenty years after the creation of the sectorial promotion regime -first in force under the Software Promotion Law (2004-2019) and then under the Knowledge Economy Law (2019-2029)- it is essential to redesign the regime with a strategic perspective aimed at promoting activities with higher added value in order to develop incipient comparative advantages. This implies considering at least four aspects.

Four issues to think about moving forward

First, the regime must have better conditionalities. In other words, the permanence of beneficiary companies must be subject to the achievement of more ambitious objectives than those currently present in the LEC. This is especially important for the largest companies, some of which have a presence in multiple countries and raise large capital investments.

Second, it is key to rethink how to improve the scope of the benefits of the regime. On the one hand, towards smaller companies. On the other hand, companies aimed at developing products for dynamic export sectors (such as those related to natural resources or the manufacturing industry associated with exports). The most likely path towards a specialized international insertion is to develop software products for sectors where Argentina is already highly competitive and that this serves as a testing ground and first portfolio of clients to then go out into the world.

Third, in this line, several countries with which we compete are advancing in co-investment mechanisms and the creation of funds of funds. It would be beneficial for the regime to have a greater involvement of the private sector, which knows the sector and the opportunities that companies have.

Fourth and finally, the redesign of the scheme must be accompanied by adequate transparency mechanisms that provide information on its coverage, operation and results. For example: who its beneficiaries are, the number of years of permanence in the scheme and the amounts received.

Creating complementary public policies in four main areas

As important as rethinking the promotion regime that is framed in the Knowledge Economy Law (in force until 2029) is to implement measures that complement it. Policies that allow the same company to develop different capacities that accompany its evolution and growth. We focus on four key dimensions: financing, internationalization, linkage with the productive network, and education and training.

Financing high-uncertainty, high-potential companies

Without an improvement in the availability and access to capital geared to fostering the long-term growth of start-up companies, it is unlikely that any progress in another dimension will have a significant effect on the whole.

Financing high uncertainty and high potential companies such as software and, in particular, product companies is not something that can be achieved through banking. It is therefore necessary to take the focus away from credit tools and put it on the capital markets. To move towards a strategy of strengthening the almost artisanal capacity of the State to design and sustain the institutional framework that in turn creates and regulates the markets.

We consider it important that private actors -and not the State directly- play the leading role in financing investment, but, even when it is proposed to generate “more market”, more rules are needed -not less-, more and better regulatory capacity.

Knowing target markets and potential international customers

A central piece of the new map of ideas should be the prioritization and focus of the internationalization policy agenda. Changing the paradigm in this dimension implies working so that the national agency and the subnational agencies dedicated to the internationalization of Argentine companies are strengthened to acquire sectorial expertise on software.

Knowing the target markets and potential international clients for the software developed in our country is not a task that can be left entirely to the market: it requires capable state institutions that are not generalists in the exporting objective, but that understand the particularities of this specific industry. Every year that the country lets pass without strengthening and providing sectorial expertise implies a huge loss of potential exports.

Increasing integration with the national productive fabric

Changing the paradigm also implies thinking that, as is done with the industrial policy aimed at developing local suppliers for other productive chains, there can be a policy focused on generating productive linkages for the software sector.

This industrial policy, with its incentives to increase national integration and the proportion of national components in final products, should not have an “internal market” logic. We must move away from an import substitution mentality: it is not a matter of importing less software from abroad, but of collaborating so that the nascent Argentine software companies can have their first field of experimentation and client portfolio at a local level and then, from there, seek their international insertion.

Promoting the formation of skilled teams

Education and training policies for the sector have typically aimed at incorporating tens of thousands of new “generic” programmers into the labour market. While these actions contribute to the growth of the sector and offer valuable opportunities for the people who are trained in this way, these types of interventions reproduce the mentality of Argentina as a producer of solutions based on the least sophisticated links.

To promote the formation of skilled teams, such as those needed by these third-generation companies, we believe that two moves must be made. First, to diagnose bottlenecks in the specific profiles required and focus the efforts of a public-private training system there. In other words, move away from the tendency to train generalists and involve the private sector in the management and financing of the training system.

Second, implement policies to support software startup founding teams and strengthen their capacity to develop exporting businesses. Many high-potential startups are made up of teams with world-class technical knowledge but with a deficit of entrepreneurial skills. Targeted public intervention in this regard can have a high impact at low cost to the State.