The textile-apparel industry has a lot to tell. The sector generates revenues of more than 16,000 million dollars along the entire production chain and in different parts of the country. What are the characteristics of this industry? What is the sector like? An overview of the textile-apparel industry in Argentina.

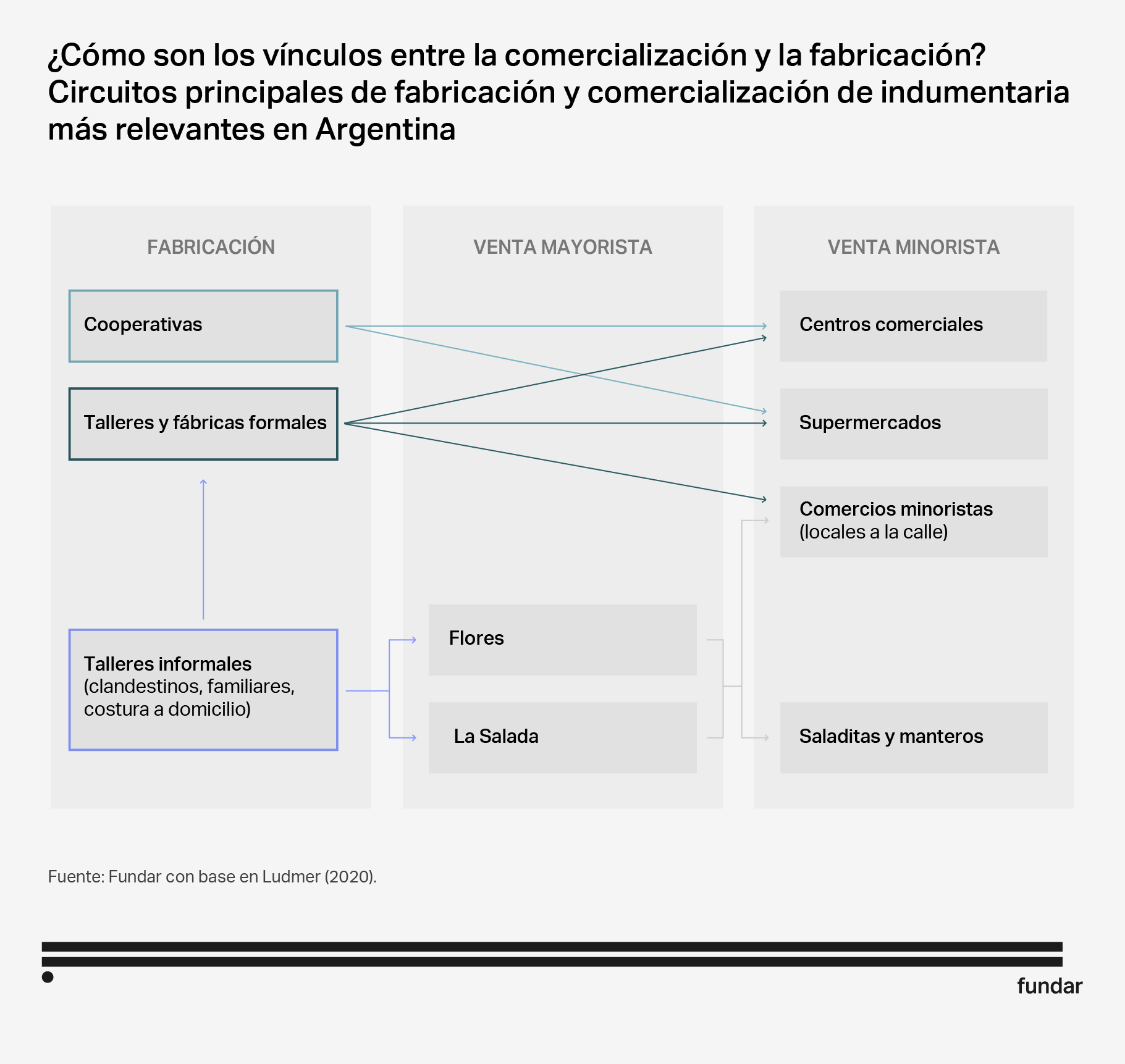

The textile-apparel industry in Argentina is characterized by a diverse landscape of manufacturing and marketing circuits that coexist and overlap. The primary wholesale circuits are Flores and La Salada, which supply garments to retailers throughout the country and serve middle and low-income consumers. However, the market extends beyond, encompassing national brands in shopping malls, targeting higher-income consumers with unique designs. Distinctions between these circuits go beyond price and consumers’ income level, encompassing levels of formality in sales and manufacturing conditions.

Local consumption: how much is spent on clothing in Argentina?

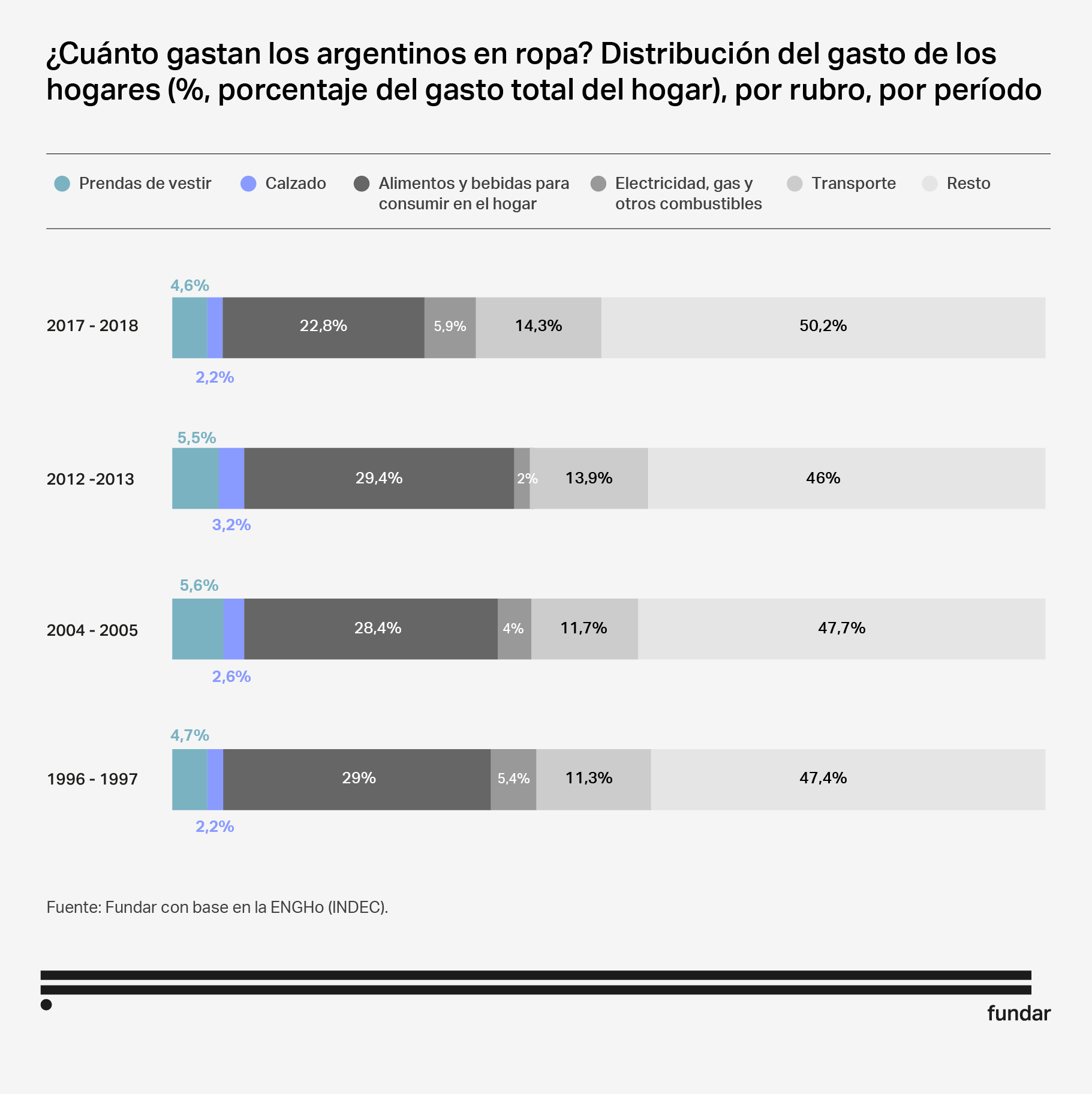

Examining local consumption habits reveals clothing as a significant consumer good for Argentinians, ranking just behind food, beverages, and transportation. In 2018, Argentine households allocated 6.9% of their total expenditures to the purchase of clothing and footwear, surpassing regional counterparts like Mexico (4.8%) and Chile (3.5%).

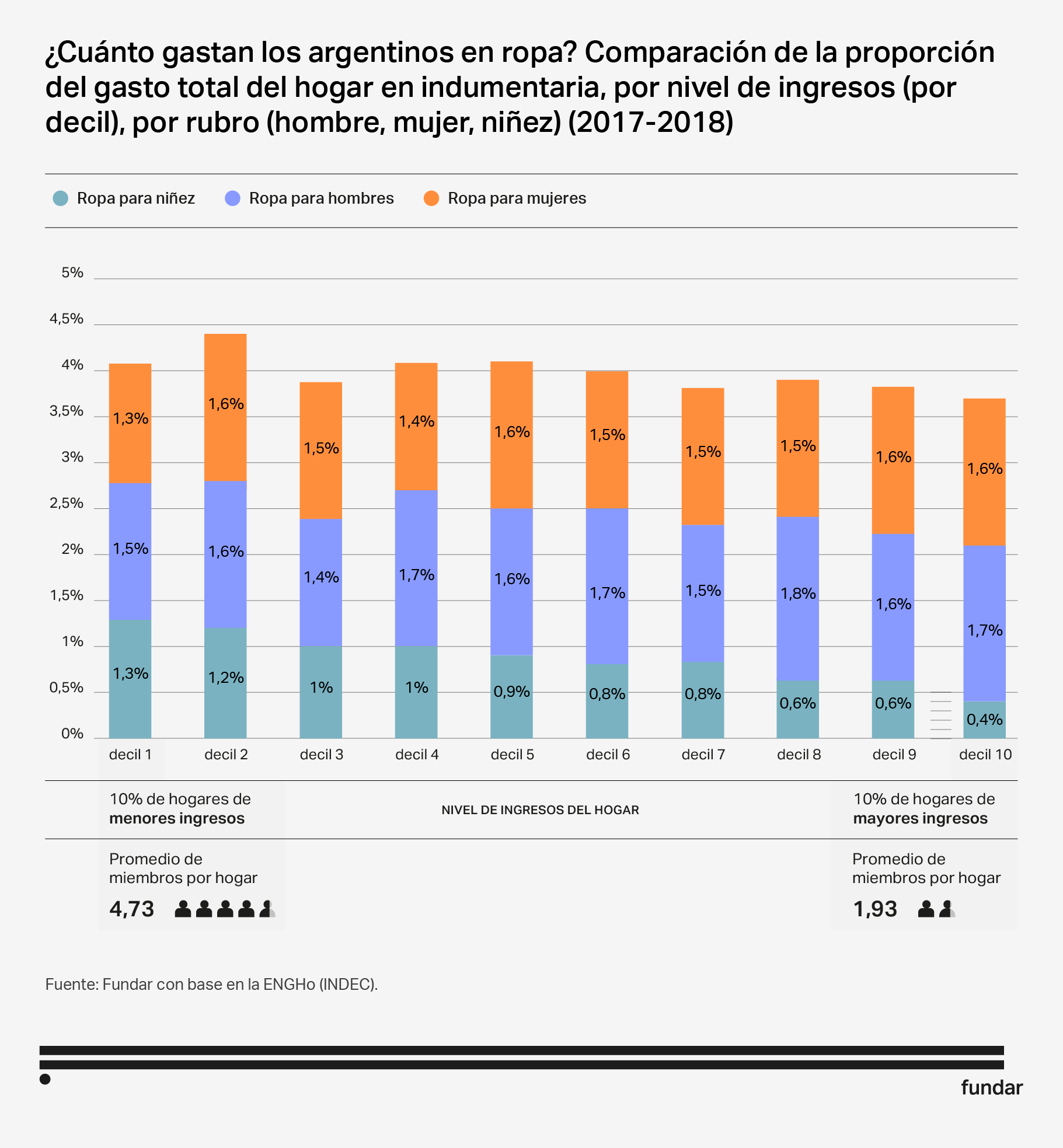

At the same time, there is a considerable disparity in spending across income levels, with lower-income households allocating proportionally more to clothing, partly explained by larger household sizes, given that lower income households have 4.73 members on average against 1.93 in higher income households. Lower-income households spend a higher percentage of their income on children’s clothing, while higher-income households allocate a greater proportion of their budget to women’s and men’s apparel.

Retail: where are clothes sold and bought?

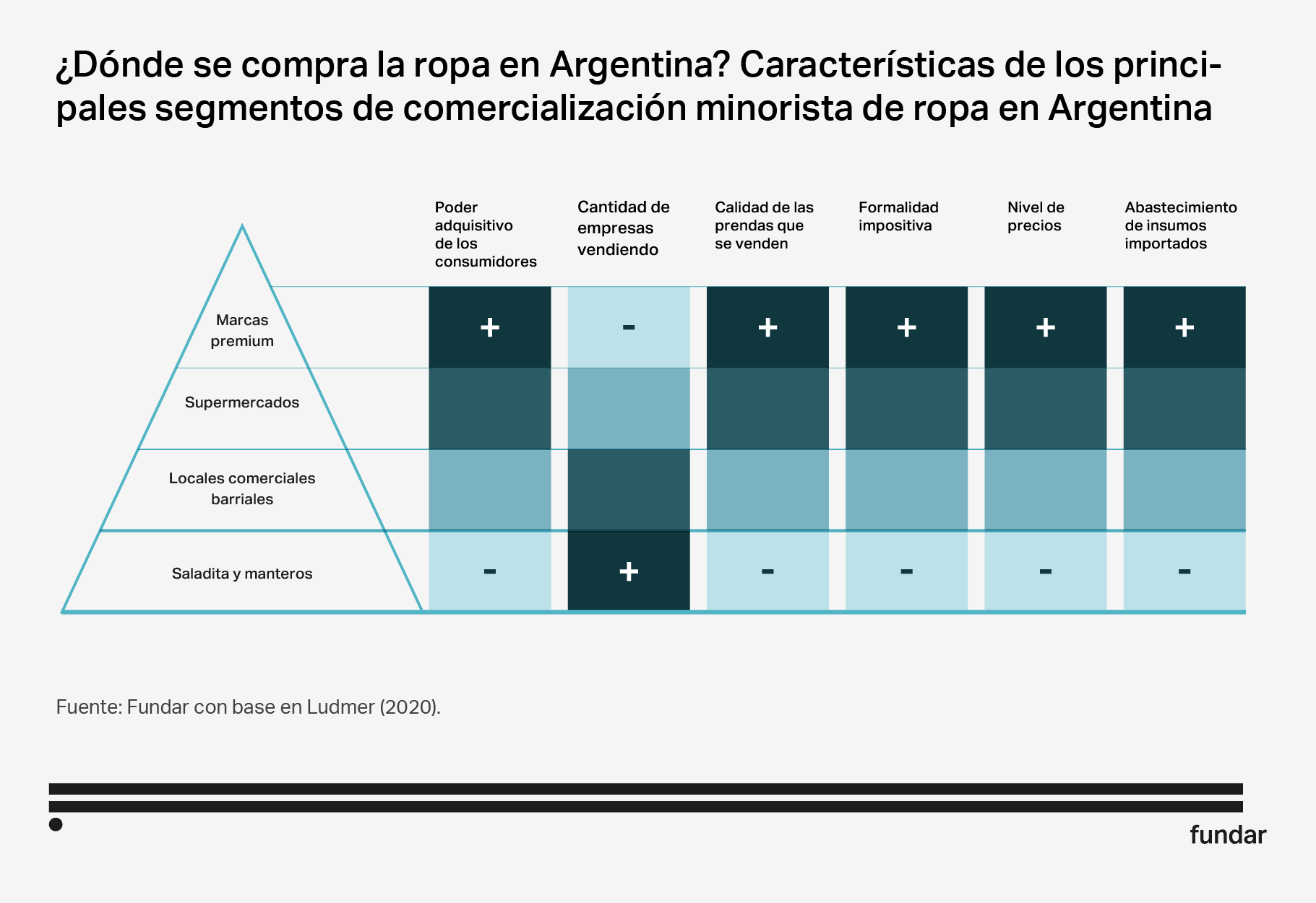

The retail industry reflects this diversity, with a wide range of stores catering to a broad spectrum of consumers. These include shopping malls, large retail chains, showrooms, supermarkets, local stores, informal neighborhood fairs (known as ‘saladitas’), and street vendors (known as ‘manteros’). This array of businesses serves consumers with varying incomes.

Premium brands and large retailers (shopping malls)

The premium brand segment, which consists of approximately 100 brands, emerged in the 1990s in response to changes in consumer habits and social differentiation. These brands are marketed in shopping malls and target consumers with high and upper-middle incomes.

Premium brands distinguish their products through meticulous design, superior quality, and a diverse array of garments. They commit substantial resources to design, branding, and robust marketing strategies.

The funding necessary to support these endeavors presents a barrier to entry for potential new players. As a result, this exclusive segment remains relatively small, accounting for an estimated 15% to 20% of market units. Unlike other Latin American markets, typically dominated by international brands, the majority of these premium brands are domestically owned.

Premium brands exhibit high levels of tax compliance in their sales, ranging from 80% to 100%. This commitment stems from various factors, including their presence in shopping malls, which makes them subject to potential operational audits. Furthermore, the prevalence of credit and debit card transactions in these large establishments adds an additional layer of transparency, contributing to their adherence to formalities. This explains, in part, the price differential with the more informal segments of the market.

Supermarkets

Supermarket chains account for only 1.5% of total apparel sales. In 2022, these establishments sold 62.297 billion pesos worth of apparel, footwear, and home textiles.

In Argentina, supermarkets sell clothing from their own or lesser-known brands at significantly lower prices and quality than those found in shopping malls. This is aimed at middle and lower-middle income consumers.

Regarding the origin of the garments, they are typically a combination of imported and locally produced items. As with premium brands, it is influenced by the value of the dollar and by the retailer’s business policies. In fact, the most important supermarket chains in the country are among the largest clothing importers, just behind the large international retail stores (Zara, Adidas, Nike, among others).

Wholesale: where is clothing sold?

In Greater Buenos Aires, wholesale clothing distribution is concentrated on two major wholesale circuits: Flores and La Salada. These supply garments to national retailers catering to both low- and middle-income consumers, gradually gaining prominence over the dated Once circuit since they were first established in the 1990s.

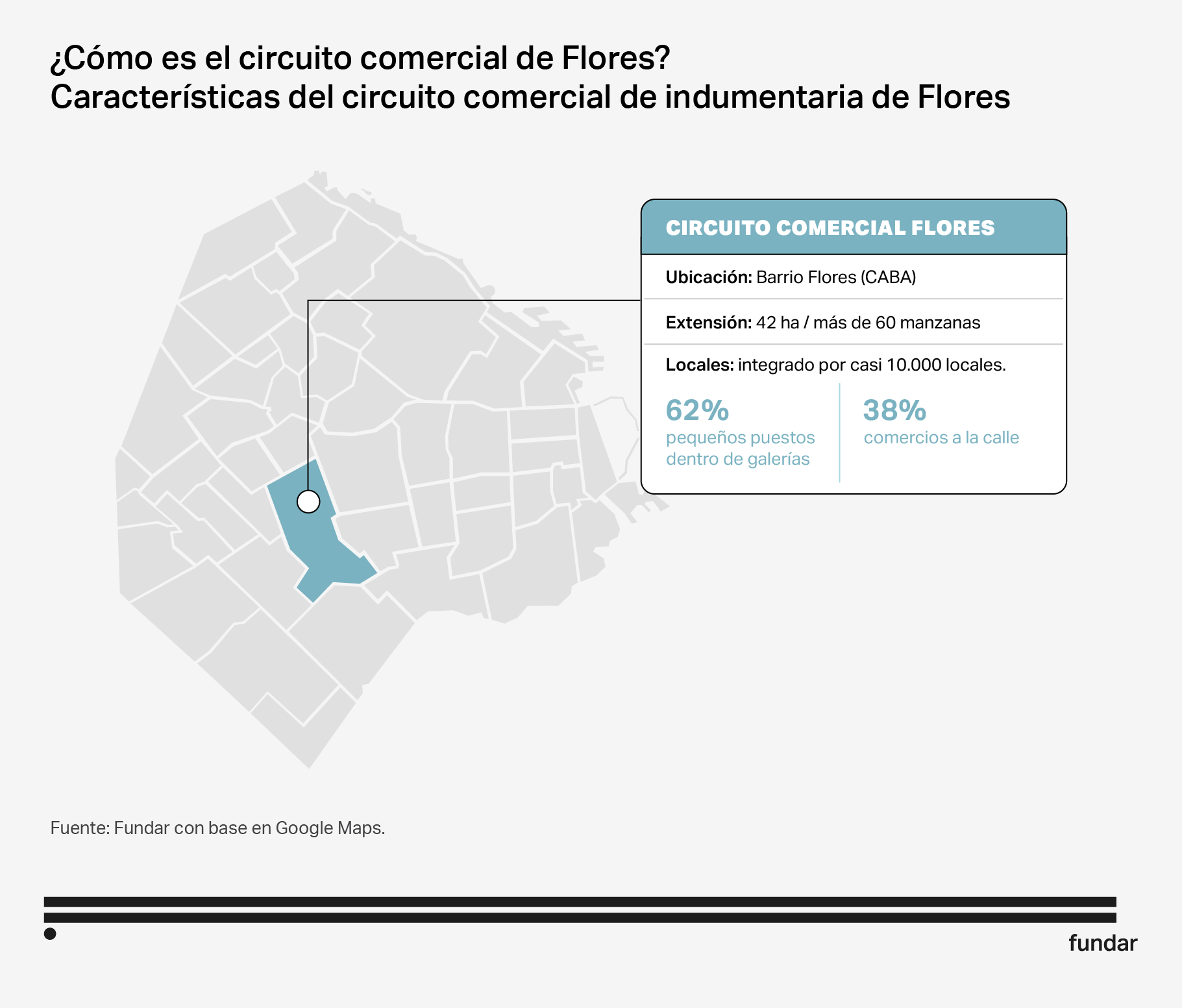

The Flores commercial circuit

This commercial area spans over 60 blocks and nearly 10,000 stores. 62% are small stalls nestled in galleries and the remaining 38% are street-level stores. Most of the street shops are part of an integrated production process, with fabric cutting often taking place on the first floor. In contrast, galleries’ stalls typically function as resale points for street stores or even manufacturers from other circuits, particularly La Salada.

With roots in the 1970s, Flores saw an influx of the initial clothing stores, predominantly owned by members of the Jewish and Syrian-Lebanese communities. The growth of the circuit accelerated between 2003 and 2011, evolving into a central hub supplying affordable clothing to retailers nationwide.

Flores is known for its ethnic diversity in the clothing manufacturing and sales industry. Approximately 30% of the community is of Korean descent, another 30% is composed of members from the Jewish or Syrian-Lebanese communities within the Argentine community, and an additional 30% is of Bolivian origin. The remaining traders come from the Peruvian, Chinese, and Paraguayan communities.

The low prices of the garments are mainly due to approximately 50% tax evasion on sales and the prevalence of informal labor in garment manufacturing.

Estimates indicate that Flores and La Salada concentrate a substantial market share of 60% in terms of quantity and 40% in terms of overall value.

La Salada's commercial circuit

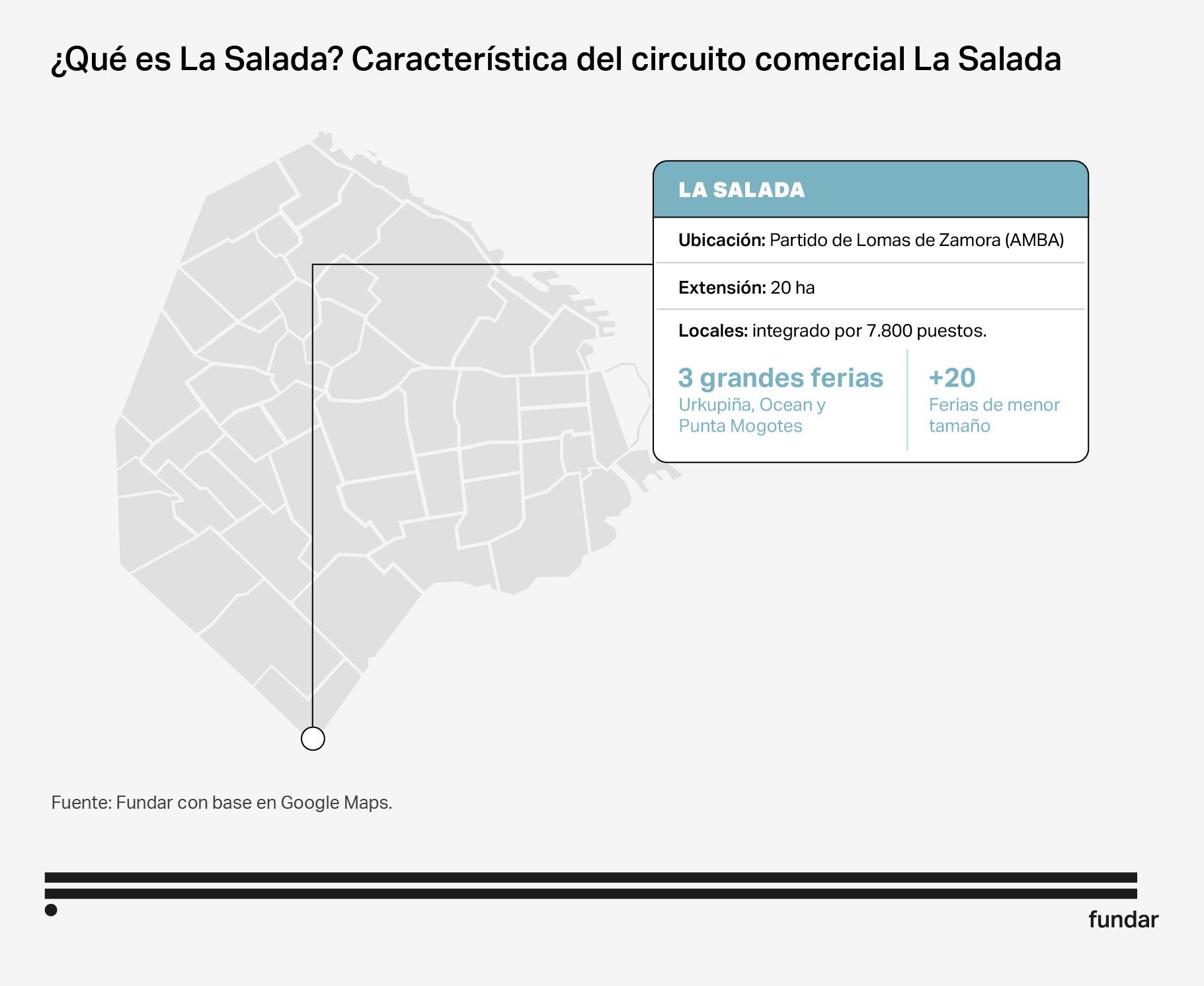

La Salada stands as one of the largest fairs in Latin America. Spanning a 20-hectare fair complex in the Lomas de Zamora district, just 30 minutes from downtown Buenos Aires, it sells clothing at low wholesale prices. It comprises 7,800 small stalls distributed across three major fairs (Urkupiña, Ocean and Punta Mogotes) along with 20 smaller fairs.

Founded by members of the Bolivian community disenchanted with meager incomes earned from producing clothing for third parties, La Salada emerged in 1991 when they organized themselves to buy the first premises. Originating as a street-based enterprise, it evolved into an organized entity, spurred by growing unemployment and income deterioration throughout the 1990s (Ocean opened in 1994 followed by Punta Mogotes in 1999). The post-convertibility era marked the peak of its activity, driven by increased consumption by popular classes.

La Salada is also home to merchants from different communities, with approximately 50% comprising first or second-generation migrants from Bolivia, nearly 25% from Argentina, 20% from Peru, and 5% hailing from Paraguay, Colombia, Korea, and Senegal.

La Salada sells domestically manufactured clothing at very low prices for several reasons. Firstly, most stallholders are also manufacturers, which eliminates intermediation costs. Secondly, the pervasive tax informality in sales and the avoidance of social charges, both in manufacturing and marketing, contribute to cost reduction. Lastly, the general quality of products tends to be modest, often featuring defective stitching.

This vast marketplace serves diverse retail traders, “saladitas” fair vendors, and “manteros” from across the country, targeting lower-income consumers. Its clientele predominantly consists of individuals with middle to low-income backgrounds, and its operations are characterized by a high degree of informality.

Garment workshops: what is the link between manufacturing practices and marketing?

The marketing practices of each of these spaces are directly associated with each segment’s manufacturing particularities.

Commercial segments with higher levels of sales tax compliance need to manufacture in formal workshops and factories that issue invoices. For this reason, most nationally manufactured garments marketed by premium brands tend to be manufactured in formal production units. In turn, this greater tax and labor formalization partly explains the higher prices of their garments, which in turn are sold to higher-income consumer segments.

In contrast, clothing aimed at low and middle-income consumers, particularly those sold through La Salada and Flores, frequently come from informal sources. This phenomenon is twofold: consumer sales’ tax avoidance impedes the absorption of tax costs related to formal manufacturing units, and these garments often lack brand recognition, originating from clandestine workshops. Intense competition among numerous suppliers in these market segments fuels a race to minimize prices, hindering the formalization of workers in sewing or sales roles

Between these contrasting segments stand the cooperatives that usually supply several market players, including brands, supermarkets and retail stores. Notably, these cooperatives find their main clients in government entities at the national, provincial and municipal levels. Many such cooperatives manufacture overalls, aprons, sanitary wear and work clothes, catering to public tenders.