Argentina has not been able to lower its poverty rates for a decade. To achieve this, successive governments have bet on increasing social investment. Although increasingly fragile, this strategy has been successful in containing people in an economic context that pushes them downward. However, it has not been very effective in promoting upward social mobility. The challenge ahead is not to cut investment, but to redesign it to improve its quality, efficiency and equity. To this end, this report analyzes how social investment has evolved over the last 20 years and what adjustments could be made in the future.

A document written by the CIAS University Institute together with Fundar.

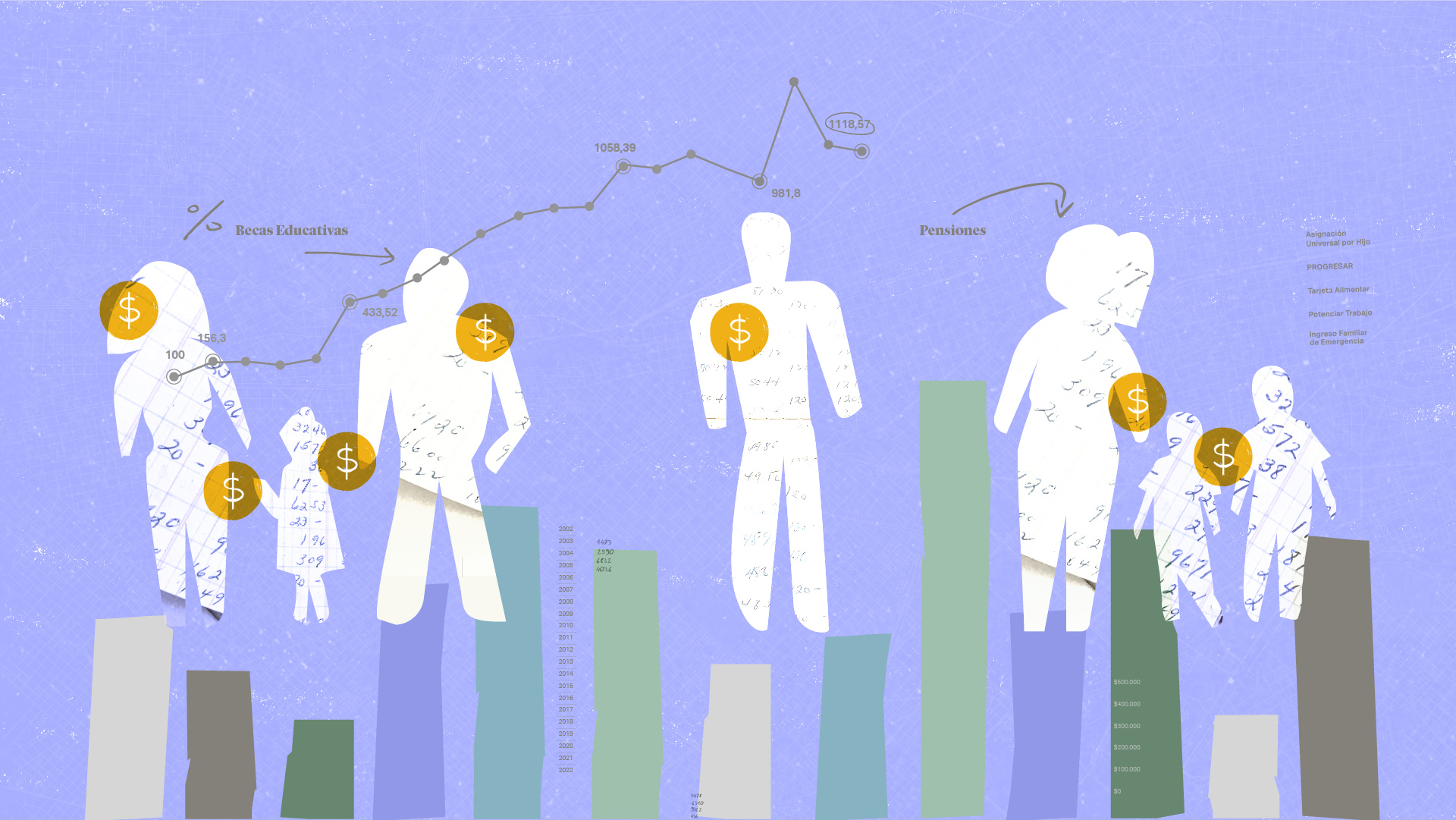

Illustration: Micaela Nanni

A social investment that contains, but does little to transform

The country has not been able to lower poverty levels for more than a decade. During this period, investment in direct and urgent social aid also grew. Between 2014 and 2022, the budget allocated to social programs increased by more than 25%. Successive governments have bet on increasing investment to make up for the insufficient creation of genuine employment and to contain the population in the face of the harmful effects of economic stagnation and inflation.

This growth in social investment plays a central role in containment. But, in recent years, it has not played a transforming role. It shows important limitations in its capacity to improve the structural conditions of the poorest people. Currently, social policies are not designed to promote upward social mobility and allow families to escape structural poverty, transition from informal to formal employment and, eventually, aspire to move up to another social class.

The challenge ahead is not to cut social investment but to redesign it to improve its quality, efficiency and equity. Along these lines, the main objective of this report is to understand the evolution and composition of social investment over the last 20 years and to generate inputs and proposals for its redesign.

Social map of social policies: new edition

The first version of the Social Policy Map was published in 2021. This new edition presents new features. On the one hand, it expands the temporal coverage (now up to 2022) and incorporates the analysis of the first years of Alberto Fernández’s term of office and specifically the administration of social policy in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, it adds two new dimensions of analysis: demographic and fiscal. A central finding of the previous report was the imbalance between investments for the elderly and those for children. In this edition, we group and analyze social programs according to the age segments they target. In addition, we examine the magnitude of the programs concerning the size of the economy and the national government budget.

The Map presents a quantitative and “top-down” analysis of social programs. It is completed with the Popular Neighbourhood Monitor, an on-the-ground study of the perception that families have of the existing network of public services and how it helps (or not) in this fundamental task of care.

Key findings on social investment

What is the overall assessment of the behaviour of investment in social programs in recent years? What are the problems (and segments) that are still not sufficiently addressed by social policy in Argentina? What aspects of social policy design could be modified to improve its equity and efficiency?

Increasingly broad but shallower coverage

If we look at the evolution of the number of social assistance benefits granted, as a matter of urgency, we see that this has grown at an accelerated pace over the last 20 years. This number has quadrupled between 2002 (3,509,493) and 2022 (13,664,392). And, even if the number of benefits does not directly correspond to the number of beneficiaries (the same person can receive more than one benefit), the trend is increasing.

Now, if we look at the evolution of the actual amounts received by the beneficiaries of each program, we observe the reverse trend. The level of benefits has deteriorated considerably over the last few years. In fact, in all programs in all but one investment category, the purchasing power of benefits is decreasing. In other words, the social safety net covers more and more people but provides less and less to each of them.

The only exception to this rule is the case of family allowances, due to the merger of AUH and Tarjeta Alimentar. As in the rest of the other programs, between 2015 and 2022, the number of AUH beneficiaries increased and their benefits fell. The big difference was made by the creation of the Alimentar Card, which functions de facto as an increase in the AUH.

Within the general dynamics of the expansion of social safety net coverage, children seem to have been the only ones favoured in terms of what they receive.

Social investment in children increased

A central problem we had identified in the previous report was the low investment in social policies aimed at children, compared to those aimed at other age segments.

In 2009, for every peso spent on poor children, 7.24 pesos were spent on the elderly. This gap has been narrowing and has changed significantly since the pandemic. Since 2020, social assistance for children has increased significantly, especially due to the creation of the Alimentar Card.

A greater social investment in children seems to us a desirable objective, especially considering the higher incidence of poverty and indigence in this segment and the critical consequences that the inadequate satisfaction of basic needs at early ages may cause.

The flip side of this substantial increase in social investment in children has been the strong adjustment on retirees and pensioners, who have seen their income decrease since 2017. This segment is in a worrying situation in the face of a pension mobility law that is inadequate to protect their income.

Low social investment in formal labour promotion policies

This greater balance of social investment between age categories coexists with significant imbalances between social policy areas. Of particular concern is the low investment in policies to promote formal employment, a problem that has existed for some time and has worsened in recent years.

The imbalance between investment for workers in the informal economy (encompassed under “cooperative plans”) and investment in programs for the promotion or preservation of formal employment has increased sharply in recent years. If in 2015, 2.5 pesos were invested in cooperative plans for each peso destined to promote formal employment, such ratio rose to 17.45 in 2022.

We believe that the State should not abandon the objective of formalizing individuals. It must contribute to the formalization of both individuals and productive units of the popular economy. Currently, the design of social programs hinders this transition. Therefore, a future reform of Argentina’s social protection system should not only increase investment in the promotion and preservation of formal employment, but also redesign some of these plans to facilitate the transition to formality.

The scarcity of social investment (and programmes) targeted at the youth sector

Young people between 18 and 24 years of age seem to be one of the age categories with the lowest specific investment.

The two main ways in which young people from vulnerable sectors can increase their chances of escaping poverty are through education and formal work. With respect to education, lower-income youth need a monetary supplement to be able to complete their studies.

The real amounts of the PROGRESAR educational scholarships were decreasing and by December 2022 the benefit of a scholarship was 9,477.73 pesos. With these values, it is difficult to think that a young person from a humble home can devote himself to study supported exclusively by this scholarship. In addition, it is worth considering that the school attendance rate is 87% for young people between 15 and 17 years of age with lower incomes, well below the average of 99.8% for those with higher incomes.

Another way for young people to escape poverty is by obtaining formal employment. However, as we pointed out earlier, subsidies for this area are not an important item either. In turn, young people are the age group that faces the greatest obstacles to entering the labour market. While the unemployment rate for the general population in 2022 was 7.1%, among young people between 14 and 29 it was 16.6%.

Unlike the other age categories, the youth segment today does not have a set of specific public policies aimed at fostering their social integration. This is a critical stage in development and a moment in which many people define their labour trajectories. In the context of growing poverty, we believe that more active support from the State is necessary.

Two keys to rethinking social investment

In a country that has achieved a very broad level of Welfare State coverage, it is necessary to move to a stage of fine-tuning in the design, implementation and impact measurement of these programs, to improve the capabilities and resources of the popular sectors and, thus, achieve significant and lasting changes in their lives.

This implies, in the first place, the urgent need to invest more resources in analyzing the impact of social programs. Unlike other countries in the region, Argentina has a wide variety of social programs that sometimes overlap in their objectives without an articulated strategy. Increasing knowledge about the impact of the various programs would allow us to improve their design, make resources more efficient and avoid overlapping.

Secondly, it is necessary to reform areas of social programs to increase people’s capacity so that these changes can be significant and long-lasting, with the transition to the formal labor market as a goal.

This link provides access to the data repository used in this report. It contains the databases that have been used to generate the analyses presented in the document. The databases present real and nominal amounts and as a percentage of the national budget for social items and programs, as well as the number of beneficiaries and the level of benefit of the programs. The data sources are the open budget portal of the Ministry of Economy (through the Open Budget Portal), the Ministry of Social Development, the Ministry of Labor, ANSES and the National Disability Agency (through requests for access to information) and INDEC, prepared by the authors.