The task of social policies is not only to contain families, but also to make a future possible. In this sense, caring for children so that they can develop and actively integrate into social life is fundamental. In order to carry out this task, families mobilize resources obtained from the market, the community and the State itself through its policies. This paper seeks to know the perception that households in poor neighborhoods of the AMBA have of the existing network of public services and how it helps (or not) in this fundamental task of care.

A document written by the CIAS University Institute together with Fundar.

Illustration: Micaela Nanni

Generating the conditions for upward social mobilit

Fostering the full development of children requires that families have resources to accompany their growth. Current social policies provide a support network that sustains basic needs, but the perception of families is that the network of public services is not providing answers to the needs and problems they experience in raising their children.

What is at stake is not only the current sustainability of families, but the possibility for them to invest in care and create future opportunities for those who are growing up. While it is necessary to sustain and improve income transfer schemes, it is also necessary to go beyond them. It is necessary to prioritize investment in infrastructure services that guarantee access to education, health, security, culture and sports, key aspects for full development.

The social monitor: a qualitative study of the impact of social investmen

To identify the problems of the current social investment system and think about future changes, it is not enough to look at it “from above” and see the composition of investment or its coverage. It is also essential to go the other way around and analyze public policies starting from the places where they become a reality for people.

For this reason, the CIAS University Institute and Fundar decided to complement the work carried out in the Map of Social Policies with this territorial report. To this end, we surveyed more than four hundred families and semi-structured interviews with fourteen community leaders in five neighbourhoods of the AMBA.

This work investigates how families use and evaluate social policies in terms of the parenting processes they carry out. Approaching the subject from this perspective implies examining the contribution that these policies make to parenting activity and its results, that is, promoting the development of an autonomous life and the integration of children into social life.

What is the role of social programmes in poor neighbourhoods?

Families spend most of their time on care work

If we analyze the use of time in the households surveyed, we see that they spend an enormous number of hours per day caring for dependent minors. The demands of these unpaid tasks limit the active insertion in the labour market of those responsible for them (almost entirely women). In this scenario, social plans operate as a labour activation tool providing work alternatives, fundamentally community work, in schedules compatible with parenting.

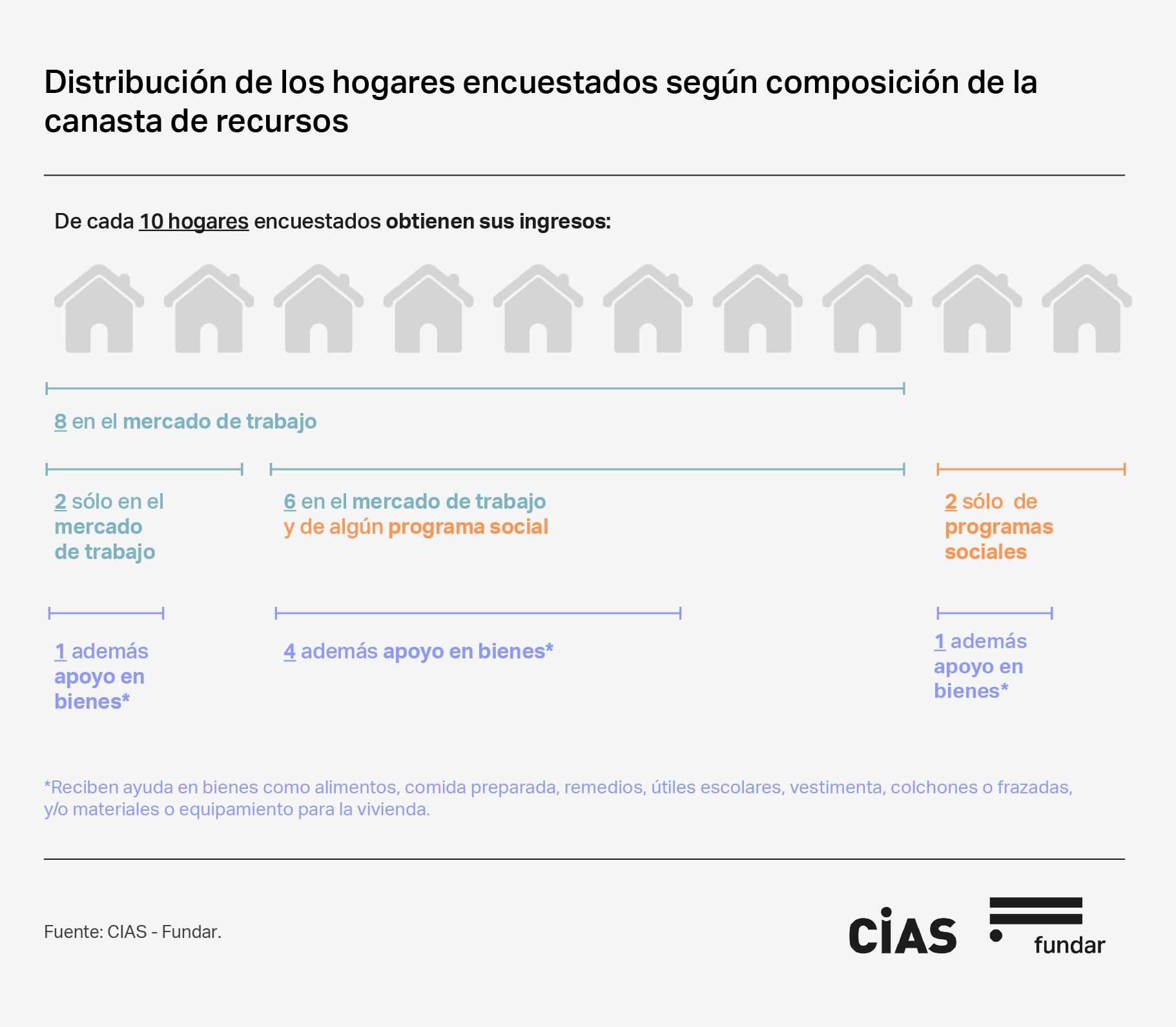

To subsist, households in poor neighbourhoods combine income from different sources

Families in poor neighbourhoods use resources from different sources to obtain the goods and services they need to care for their families. In almost all of the families surveyed (95%) at least one of their members obtains income from some type of work activity. In 78% of the cases, this income comes from the labour market, the rest from state transfers associated with community tasks financed, above all, through the Potenciar Trabajo program. Families supplement this income with the AUH (70%), the Tarjeta Alimentar (49%) and programs for young people (especially PROGRESAR 7%).

This set of resources is essential for families today. Any abrupt alteration in employment levels, in the value of transfers, or the availability of food exposes them to a limit point. As the Social Policy Map 2023 suggests, the interviews support the need to sustain a safety net in the current situation. Its elimination or liquefaction puts families at risk.

What resources do families in poor neighbourhoods have?

The return on family working time, both paid and unpaid, depends not only on the current resources available but also on the physical and human capital that families have managed to accumulate.

Vivienda

In terms of physical capital, the first feature that stands out is the precariousness of housing. The interviews describe it as a phenomenon that accumulates intergenerationally. The children do not abandon the house but build on the same land. It is common to find three or even four generations living on the same property.

The precariousness of housing is not only expressed in the lack of autonomy and privacy, but is also felt in the upbringing of children. The house is not a place where they can develop their activities and, as an alternative, there is often only public space.

Human capital and accumulated skill

In addition to the precarious infrastructure, there is a history of low accumulation of human capital, in terms of family care and schooling, in the adults responsible for care. Moreover, just as investment in infrastructure must be postponed to cover the current costs of care, so too must investment in the human capital of the caregivers themselves be postponed due to insufficient time and income.

On the one hand, the survey shows that female heads of household left their home of origin at an early age. Almost half (46.2%) left before the age of 18 and 60% before the age of 19, postponing studies and projects. Leaving home is explained by early motherhood in 56% of the cases and, in 13%, by family conflicts.

On the other hand, although female heads of household and their spouses improve the educational levels of their parents, more than 70% still have not finished high school.

What role does public infrastructure play for families in poor neighbourhoods?

No family could develop the capabilities of its members only with its resources (physical and human). The achievement of expected educational levels, health care and sociability require infrastructure and public services that families can access. The availability of this capital is as, if not more, critical to their activity than family capital itself.

In recent years, social and urban integration policies in poor neighbourhoods have begun to gain a place on the public policy agenda. Their support and expansion is essential for families to be able to carry out successful child-rearing processes. In fact, infrastructure problems and access to basic services appear at the top of the families’ concerns. And, with differences depending on the neighborhood, if they could choose and prioritize the type of assistance and investment, they choose infrastructure and services.

The survey shows the serious problems that the families see in four fundamental services: school, health, security and sociability spaces. According to their perception, their needs do not find sufficient answers in these services, which are so fundamental in the upbringing and care processes.

School

Among the services that families consider a priority for improvement, educational services are in first place. In the view of caregivers and adolescents, schools appear to be overwhelmed and, in many cases, do not provide an education that allows for developing skills and expanding opportunities. The most frequently mentioned problem is the repeated interruption of school activities, mainly due to strikes and teacher absenteeism. The other problem is violence. Institutions are described in which authority relations are very weakened, with little capacity to prevent and control situations of daily violence.

Health

The second priority is health services. In this area, the problems focus on the difficulty in accessing appointments and the lack of personnel and supplies in the nearest health centres. For the family, attending to health problems becomes a costly task, involving transfers to distant areas. In this context, it becomes difficult to sustain prolonged treatments.

Spaces for socialising

The testimonies show that intentionally organized spaces for sociability have a relevance equivalent to that of the school and the health centre. Although community organizations seek to make up for the lack of these spaces, the street and the corner continue to be the places most inhabited by adolescents and young people. This exposes them to an environment marked by violence and insecurity. Existing policies and the efforts made by community organizations need to be taken to another level to ensure not only greater coverage but also a quality proposal that is attractive.

Eight guidelines to strengthen public policy

Based on the results obtained, we present eight guidelines to strengthen public policies and social programs in poor neighbourhoods.

- Strengthen transfer programs, which keep families in operation.

- Sustain and deepen investment in urban infrastructure and basic services.

- Improving and strengthen schools, a relevant aspiration when thinking about upward social mobility.

- Improve and strengthen health centres.

- Invest in spaces for socialization and recreation (sports and culture).

- Invest in security as part of a policy of development and recovery of public space.

- Invest in caregivers: strengthen spaces and opportunities for the development of the people responsible for caregiving.

- Strengthen (not weaken) state capacities at different levels and sectors, as well as coordination, articulation and governance mechanisms.