Bioeconomy is presented as a new techno-productive paradigm with great potential to harmonise development and environmental sustainability in Argentina. The province of Misiones could be an example of this approach. The productive particularities and abundant biological resources of the region give it a competitive advantage for the development of agricultural bio-inputs, the installation of forestry biorefineries and the implementation of payment for ecosystem services schemes. These transformative activities could dynamise the provincial productive structure and promote the protection of local ecosystems.

Bioeconomy as a sustainable development strategy

The environmental crisis imposes new challenges on us when thinking about an economic development strategy for Argentina. The identification and selection of activities that could lead this process should no longer be based exclusively on their capacity to generate foreign exchange, foster innovation, generate employment and productive linkages. It is equally important to consider the potential of these activities to contribute to mitigating and adapting to the environmental crisis.

In this context, the concept of the economy has gained prominence on the international agenda in recent years. The economy is associated with the use and transformation of resources of biological origin (not only biomass such as crops or wood but also genetic resources and organisms, for example) from nature for the production of goods and services, based on the intensive application of scientific and technological knowledge. How can the economy contribute to the design of a sustainable development strategy?

Firstly, the economy has the potential to modernise and improve the productivity of traditional activities through the incorporation of advanced technologies, such as green chemistry, modern biotechnology and nanotechnology. Moreover, these technologies, which are at the core of the economy, are often seen as key players in the next technological paradigm, opening a window of opportunity to take advantage of the benefits of adopting a new development in its early stages. To get a dimension of the potential of this strategy, it is estimated that up to 60% of the materials currently used in the global economy can be replaced by bio-based products (Chui et al., 2020).

Second, the bioeconomy could represent a way out of the false environment-development dichotomy. It is often argued that economic growth may compromise the future habitability of the planet. On the other hand, it is argued that developing countries cannot afford to forego improvements in present well-being in the face of high levels of poverty and material deprivation. A bio-economy-based development strategy can promote a low-carbon and circular economy, based on the use of biological resources and the reuse and recycling of materials, including waste from primary and manufacturing activities. In certain contexts, the bioeconomy also generates value through the conservation of ecosystems, which in turn provide ecosystem services (those benefits that an ecosystem generates for society and the economy). In turn, this approach is compatible with other emerging global valuation practices, such as the development of carbon credit schemes, green bonds, payments for ecosystem services and ecotourism strategies.

Argentina's Amazon’ as an example of bio-economic development

The province of Misiones has characteristics that provide a glimpse of an opportunity to combine nature conservation and economic growth through the economy. Its biodiversity and wealth of natural resources can provide biological solutions to some of the problems of its production chains.

Its natural wealth lies in its extensive forest cover, the groundwater of the Guaraní Aquifer System and the great biological diversity of the province. The importance of the Misiones forests within the Atlantic Forest is so remarkable that it can be easily identified in satellite images by its dense forest cover, surrounded by a vast area of land used for agriculture and livestock.

Considered the “Amazon of Argentina”, the province of Misiones concentrates 2.6% of the country’s native forests and 52% of Argentina’s biodiversity with more than a hundred species of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, plants and fungi. The Parana rainforest is part of the so-called Green Corridor, one of the few ecological corridors in Argentina, which crosses 22 municipalities with diverse landscapes including protected areas, agricultural colonies and native villages.

This natural wealth coexists with significant environmental challenges due to the impact of deforestation, intensive agriculture, and forest fires, among others. Globally, Argentina is among the ten countries with the greatest increase in primary forest loss between 2020 and 2022 (Global Forest Review, 2022). Specifically, Misiones ranks tenth among the 23 Argentine provinces with the greatest loss of native forests between 2007 and 2022, accounting for 1.5% of the total deforested area at the national level (the highest figures are accounted for by Santiago del Estero with 28%, Salta 21%, and Chaco 13%). It is worth noting that Misiones registers one of the steepest deforestation decline rates in the country (Centro de Información Ambiental, 2022). In addition, much of the province’s agricultural production uses conventional agrochemical-intensive production techniques, which represents a problem for health, local ecosystems and biodiversity.

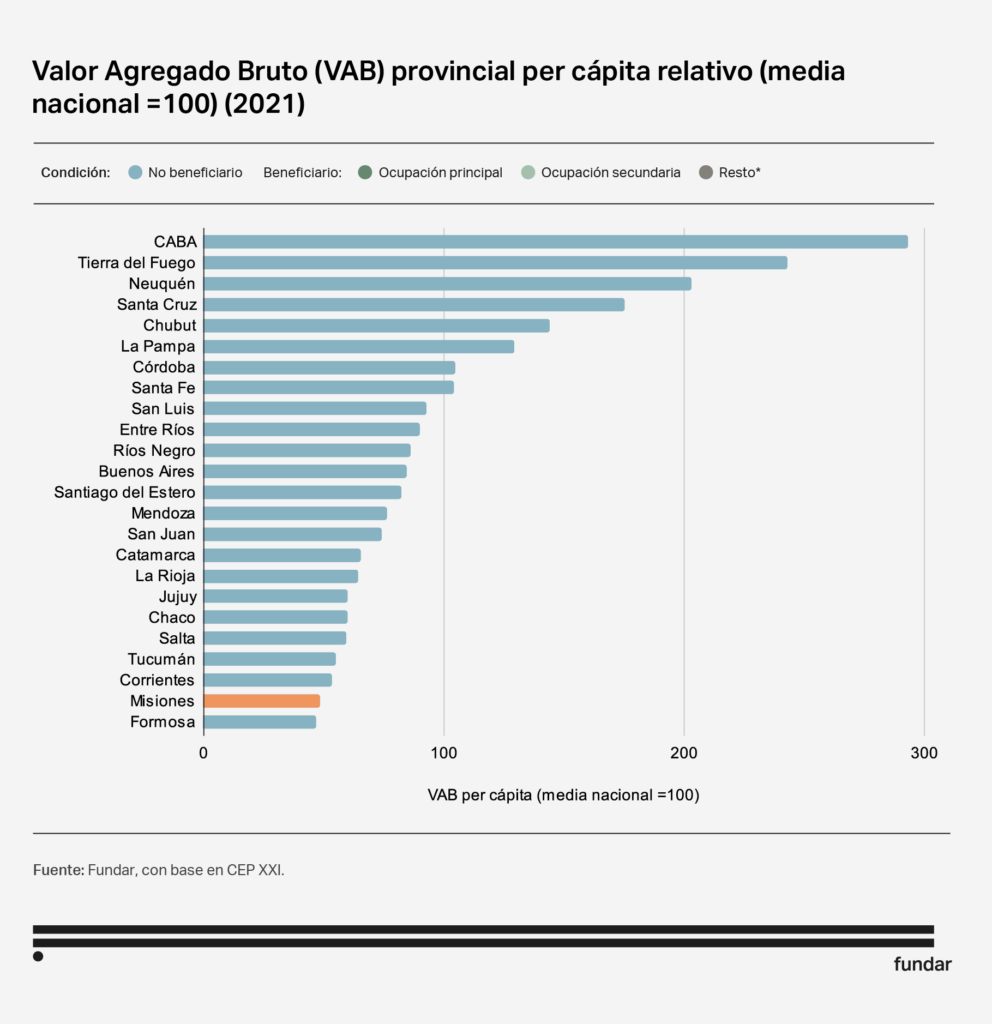

All this nature-based wealth coexists with poor economic performance. Taking GDP per capita as an indicator of development, in 2021 the province recorded one of the lowest levels of GDP per capita compared to the national level, only ahead of Formosa.

Furthermore, the characteristics of Misiones’ export basket reveal a strong concentration of the productive structure in a few sectors, many of them associated with agricultural activities with little added value. For example, around 40% of provincial exports came from the tea and yerba mate complex and 30% from the forestry complex, mainly due to the export of cellulose.

Under these initial conditions, is it possible to dynamise Misiones’ economy through the resources derived from its nature and at the same time preserve its ecosystems? Certainly, yes. The bioeconomy can act as a bridge in this sense. Now, what could be the axes of this strategy for Misiones? Based on conversations with provincial officials and a survey of previous studies (carried out in the framework of a joint project with the Federal Investment Council), three bioeconomic platforms with potential in the province were identified: agricultural bio inputs forest biorefineries and payments for ecosystem services.

Three bio-economic platforms for sustainable development in Misiones

1

Harnessing biodiversity in Misiones: the case of agricultural bioinputs

Bio-inputs are agricultural inputs of biological origin produced, derived from or composed of micro-organisms or macro-organisms, whose purpose is to improve the productivity, quality and health of plant crops.

While they still represent a limited share of the total agricultural input market (biopesticides represent 5% of the global pest control market and biostimulants and bio fertilisers 2% of the fertiliser market), they far outpace the growth rate of chemicals: while agrochemicals are growing globally by 3% per year, biological inputs are growing at a rate of 15% (Starobinski et al, 2021). The bioinputs market is estimated to reach USD 10.6 billion in 2021 and is projected to grow to USD 18.5 billion in four years. Specifically, in Latin America, there is sustained growth in the bioinputs market from USD 641 million in 2017 to more than USD 1 billion in 2021 (FAO, 2023).

Misiones’ biodiversity represents one of the province’s strengths in the development of bio inputs. One of the contributions in terms of biological solutions could be, for example, to isolate native strains of microorganisms to develop effective bio inputs for the province’s main crops.

Combined with this strength, there is a latent demand to adopt the use of bio-inputs as a new sustainable agricultural technique, which falls on local producers (mainly in the yerba mate, teal and forestry chain), which responds to environmental concerns but also to innovation and prices. Producers are currently more sensitive to the environmental crisis, partly due to a generational change in the heads of farming families, who are now more open to the use of innovative practices. On the price side, there is a search for niche markets that pay a differential price for organic production, which in the case of yerba mate can be 30% higher, according to sources consulted.

In this context of opportunities, in the province of Misiones, a productive framework is being formed around bio inputs in which different actors from the scientific and technological systems as well as from the public and private sectors interact.

Few bio-input firms in the province in terms of business actors, although with great potential.

Of the 268 companies that registered bio inputs with the National Agrifood Health and Quality Service (SENASA), only one – linked to the Misiones biofactory – is based in Misiones. However, some interesting cases show the potential for the development of a business network in the sector. A cutting-edge example for the province is the public-private company Misiones Biofactory, which produces and markets biofertilisers. In 2019, it was able to authorise a biological plant with SENASA, which allows for pilot scale-up not only for its developments but also for other institutions in the province. Part of the Biofactory’s dynamism is due to the role of the provincial government as a demander and source of financing for the company. There are also producer cooperatives such as the Caiyal Cooperative (yerba mate) and the Reverdecer biofactory that are developing biopreparations (a sub-type of bio-input) for their use but are planning to obtain SENASA approval and open marketing channels.

A network of public science and technology institutions that have played a key role in training human resources and providing technological services.

These institutions include the Montecarlo Agricultural Experimental Station of the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA Montecarlo), the Misiones Biotechnology Institute (INBIOMIS) and the Misiones Innovation Agency. Many of these entities collaborate with companies in the production of bio inputs applied to various provincial crops, although this is a more recent development. For example, INTA Montecarlo has worked on the isolation of native strains and the development of bio inputs in the laboratory with local companies, such as Misiones Biofactory, with whom they are developing a bio input to control the “Taladro” disease in yerba mate.

The provincial policy carries out various support activities to promote the production of bio-inputs.

An example of this is the enactment of the Bioinputs Promotion Law in 2023, whose implementing authority is the Ministry of Agriculture and Production of Misiones, making Misiones the first province in Argentina to have such a law. In addition, the provincial government has established the regulations and administrative circuits for the implementation of the Nagoya Protocol 1 through the Misiones Institute of Biodiversity (IMiBio) and has promoted the production of bio inputs through public purchases made by the Ministry of Family Agriculture.

Despite the potential in Misiones, there are still challenges that hinder the deployment of bio inputs in the province linked to the following points:

- Lack of technological linkages. Although there are scientific institutions in Misiones that are searching for biological solutions to some of the problems of the province’s productive chains, there is a lack of a clear circuit focused on the productive scaling and the arrival to the market of these developments, as well as a lack of experience in the creation of start-ups. Startups and few links with other companies beyond the Misiones Biofactory.

- Low availability of human resources and specialised infrastructure. Farmers in the province are trained in conventional production techniques with intensive use of agrochemicals, so they do not have access to biological solutions or to specialised technical assistance in agroecology, marketing and registration of bio inputs (in the case of those producers who manufacture their bio inputs). Furthermore, the province does not have certified laboratories where tests can be carried out for the registration of bio inputs.

- Under-exploitation of biodiversity. There is a shortage of prospective studies based on bioinformatics and omics techniques2 to explore on a larger scale the possibilities of developments based on genetic resources. On the other hand, although the regulation of access and the distribution of benefits derived from the use of genetic resources is effectively carried out in the province, control and monitoring actions on the permits granted and on the improper or unauthorised use of genetic resources have not yet been implemented.

2

Getting value from forestry residues: let's talk about biorefineries

Biorefineries are defined as establishments where biomass (organic matter in general) is transformed into a variety of marketable products and energy through a sustainable and circular production process. The term biorefinery is often used as an analogy to oil refineries. Forest biorefineries are those that have as their main feedstock the resources of the forest sector, from wood to by-products such as sawdust or tree bark.

The global market for biorefinery products is growing, reaching USD 142 billion in sales in 2022 (0.14% of global GDP). It is forecast to grow by 8.2% year-on-year over the next five years, reaching USD 210 billion in 2027 ( Mthembuet al, 2021). When looking at the different products of forest biorefineries, promising scenarios can be observed, such as wood-based plastics. Although they have a marginal share of the world plastics market (less than 1%), their production will double between 2019 and 2022, reaching 4.4 million tonnes per year (Verkerk et al, 2022).

Misiones’ potential for the establishment of forest biorefineries is based on at least two factors.

Biomass in abundance.

This is observed both in its raw material (33% of the total national area of planted forests is in Misiones, according to the National Directorate of Industrial Forestry Development) and in its by-products. It is estimated that for each harvest, only 30% of the tree is commercially exploited; the remaining 70% of the biomass is not assigned an economic value and most of these residues are burned(Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation of the Nation, 2013).

Solid scientific-technological knowledge base.

Misiones is home to a large number of scientists and scholarship holders associated with the country’s forestry industry (between 14% and 20% in 2016, according to the former Ministry of Finance and Finance of the Nation). Among the most prominent institutions is the Institute of Materials of Misiones (IMAM), belonging to CONICET and the National University of Misiones (UNaM), which has an impact on issues related to biorefineries, particularly through the Pulp and Paper Programme (PROCyP). Its objective is to research biorefineries and the pulp and paper industry. To this end, they have around 20 researchers, fellows and technical staff.

One of the most promising contributions of IMAM and PROCyP is the leadership assumed in the project to create the country’s first forestry biorefinery in Misiones, which is part of the Regional Biorefinery Centre of Northern Argentina (BioNA)project3. The biorefinery is planned to be installed on a pilot scale in the city of Posadas, within the university campus, where it will use the residues and waste generated by the forestry industry to produce a range of chemical inputs, materials and energy of biological origin. In this way, BioNA represents an important first step in the development of biorefineries in Misiones. It should be noted that BioNa is in a mature stage with certain questions regarding commercial scaling up, subject in part to the release of national public funds for the construction of the plant, already approved by the National State, according to sources consulted in 2023.

However, the following obstacles were identified for the exploitation of the province’s existing capacities and the scope of biorefinery opportunities:

- Lack of specialisation strategy. Biorefineries allow the processing of a wide range of bio-based products with applications in various industries. Given the innovative nature of these products, it is crucial to define at this stage a specialisation strategy that promotes improvements in quality and productivity and thus facilitates market penetration. This strategy should define the products to be produced, the markets in which to enter, and the regulatory obstacles to be considered, among other issues.

- Little information on this subject. There is currently no accurate, precise and centralised information on the location and available quantity of forest biomass (mainly by-products) that would allow economic feasibility studies of biorefineries to be carried out. The identification of “clusters” around biomass is of great importance to define the geographical installation of biorefineries.

- Difficulty in attracting financing. The costs associated with biorefineries are high, especially large-scale ones, both operational (they are energy-intensive operations, for example) and installation (they are capital-intensive) and the returns on that investment are uncertain given the low maturity of the market associated with biorefineries.

3

Incentivising environmental conservation practices: the case of payments for ecosystem services

An ecosystem is a dynamic system of interrelationships between communities of plants, animals and micro-organisms and the non-living environment, where they interact as a functional unit and in which humans are an integral part. Environmental services encompass all the benefits that human societies derive from ecosystems, among them:

- Natural resources such as water and food.

- Ecosystem processes that regulate conditions such as climate or erosion.

- The contribution of ecosystems to experiences that enrich societies, such as recreation or a sense of belonging.

- Basic ecological processes make the provision of the above services possible (MEA, 2003).

Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) programmes are market mechanisms in which the beneficiaries of ecosystem services pay the landowners who own the land on which these ecosystems are located to commit to conservation and restoration actions (such as reforestation, the preservation of riparian areas and the use of sustainable agricultural techniques, among others). In this way, the aim is to ensure the continued provision of these services(Wunder et al., 2007). Although ecosystems provide a variety of environmental services, PES schemes tend to focus on the protection of forests, biodiversity and water resources.

PES programmes have been developed around the world since the early 1990s. It is estimated that USD 10 billion is mobilised annually in PES worldwide(OECD, 2021).4 Latin America has been a pioneer in establishing PES schemes financed or implemented mainly by national governments. Latin America has been a pioneer in establishing PES schemes financed or implemented mainly by national governments.

The forestry sector, for example, contributes more than USD 1.52 trillion to global GDP and employs 33 million people(FAO, 2022). While this directly represents 1% of global GDP(USD 100.6 trillion in 2020), indirectly more than half of global GDP depends on ecosystem services, in particular those provided by forests. It is therefore essential to deploy a strategy for the preservation and care of forests through PES programmes.

Misiones shows the capacity to move forward with such financial schemes.

Regulations supporting PES initiatives.

These include Law XVI-103 on Payments for Environmental Services (passed in 2009), which establishes the framework for the implementation of PES programmes in line with national and provincial laws related to forests.

Actors focused on ecosystem valorisation tasks.

The province has been a pioneer in institutionalising the environmental agenda, creating the country’s first Ministry of Ecology and Renewable Natural Resources and the first Ministry of Climate Change in Latin America, for example. These bodies are responsible for formulating policies, regulations and strategies that promote the conservation and sustainable use of natural resources and ecosystems. In this way, they seek to guarantee a balance between economic development and environmental preservation.

Likewise, from the scientific sector, the Missionary Institute of Biodiversity (IMiBio) and the Institute of Subtropical Biology (IBS) are working on agendas related to the identification of ecosystem services and quantifying their contribution to carbon sequestration. At the same time, the Faculty of Forestry Sciences and the Faculty of Exact, Chemical and Natural Sciences of the National University of Misiones (UNaM) provide technical assistance and develop undergraduate, postgraduate and university extension courses oriented towards biodiversity conservation and valuation of environmental services.

Important background for the advancement and consolidation of PES focused on forest and water protection.

The payment for the water services scheme in the Campo Ramón Stream Basin is a reflection of this, which positioned the province as a local pioneer in this type of initiative. It was a project supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in the framework of the project “Incentives for the Conservation of Globally Important Ecosystem Services”, in conjunction with the Ministry of Ecology and Renewable Natural Resources of Misiones, the Municipality of Campo Ramón, the Limited Electric Cooperative of Oberá, the Argentine Native Forests Foundation for Biodiversity, INTA and the landowners. The development of biodiversity-related bonds, waste treatment certificates and a methodology for measuring carbon sequestration from cool roof coatings (reflective coatings)5 are other actions that represent relevant precedents for the province.

Misiones’ interest in implementing PES schemes for forest protection has materialised with the Environmental Services Benefits Programme (ECO2) initiative. ECO2 seeks to obtain financial resources from the international voluntary carbon market by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and degradation of native forests, issuing carbon credits. The funds obtained will be used for activities aligned with the Provincial REDD+ Strategy 6, including PES for forest owners and caretakers, conservation programmes in the Misiones rainforest, support for family agriculture and development of the knowledge industry, entrepreneurship and startups. This would be the first PES initiative for forest ecosystem conservation in Argentina.

However, despite the province’s experience and resources in implementing PES, there are still barriers to scaling up and sustaining it:

- Falta de identificación y cuantificación de los servicios ecosistémicos. No existen guías metodológicas a nivel nacional para valorizar los servicios ecosistémicos. Resulta necesario consensuar y definir formas de identificación y valorización de los servicios ecosistémicos, como así también consensuar la metodología para la medición de la captura de carbono proveniente de los bosques misioneros.

- Falta de coordinación entre distintos niveles de Gobierno y otros actores clave. Se requieren esfuerzos de coordinación y criterios unificados entre organismos gubernamentales nacionales y subnacionales con participación en la temática. Por ejemplo, la articulación con el gobierno nacional resulta clave para captar fondos del mercado internacional de carbono voluntario mediante la emisión de créditos. En este sentido, el aval de la Subsecretaría de Ambiente de Nación constituye una exigencia por parte de las certificadoras para garantizar que este cumpla con los estándares internacionales. A su vez, también se requieren esfuerzos de coordinación entre el sector privado (certificadoras y productores), la academia (Universidad Nacional de Misiones) y organizaciones y empresas internacionales dedicadas a la comercialización de este tipo de instrumentos, todo ellos claves para el escalado y sostenimiento de este tipo de iniciativas.

- Poca articulación con el sector académico y científico tecnológico, información y comunicación. Estos pueden tener un rol fundamental en la generación de conocimientos, herramientas y tecnologías necesarias para entender, medir y asignar valor a estos servicios, lo que a su vez ayuda en la toma de decisiones informadas y en la gestión sostenible de los recursos naturales.

Final thoughts

In the context of the environmental crisis, the design of economic development strategies must evolve to integrate environmental sustainability more effectively. In this sense, enhancing the economy emerges as a promising strategy as it offers a way to modernise traditional sectors through advanced technologies such as green chemistry and biotechnology, thus facilitating economic development that is not only efficient but also environmentally friendly.

In defining a bio-economic specialisation strategy, at least two complementary considerations need to be borne in mind. Sub-national focus matters: promoting a bio-economy-based development strategy in a country with a large territory and a considerable diversity of biological resources requires adopting a territorial perspective. That is, each region must design its regional development strategy based on its assets, capacities, resources, and cultural and social characteristics. There is no single successful strategy to follow, but rather each region must design its own, choosing “transformative activities” appropriate to its territory. This is what is known as “Smart Specialisation” (Foray et al., 2009).

Some of the initiatives underway in Misiones show how the economy can combine economic growth with environmental conservation. The biodiversity-rich province has the potential to transform its natural wealth into economic opportunities through the economy. Incipient progress in the development of agricultural bio inputs, forestry biorefineries and payments for ecosystem services demonstrates how Misiones’ natural capital can be harnessed to foster sustainable development.

It is important to stress that natural wealth alone does not guarantee the success of a bioeconomy-based strategy. We are facing very demanding activities in terms of financing, regulatory capacities and coordination between business, state and scientific-technological system actors. The outlining of this bio-economic strategy must be the result of a participatory process involving most of the provincial actors. All of this poses a challenge for institution-building.

This note is based on the report carried out between Fundar and the Federal Investment Council (CFI) for the government of the province of Misiones: Grosso J., Monzon J., Mendoza F., Zornada C.F., Villafañe M.F., Gonzalez Cap S. and O’Farrell J. (2024). Transformative activities for the deployment of the economy in the province of Misiones. Buenos Aires, Federal Investment Council.

References

Bullor, L., Braude, H., Monzón, J., Cotes Prado, A. M., Casavola, V., Carbajal Morón, N. y Risopoulos, J. (2023). Bioinsumos: Oportunidades de inversión en América Latina. FAO.

Chui, M., Evers, M. y Zheng, A. (2020). How the bio revolution could transform the competitive landscape. McKinsey Quarterly.

FAO. (2022). El estado de los bosques del mundo 2022. Vías forestales hacia la recuperación verde y la creación de economías inclusivas, resilientes y sostenibles. FAO.}

Foray, D., David, P. A. y Hall, B. (2009). Smart specialization–the concept. Knowledge economists policy brief, 9(85), 100.

Grosso J., Monzon J., Mendoza F., Zornada C.F., Villafañe M.F., Gonzalez Cap S. y O’Farrell J. (2024). Actividades transformadoras para el despliegue de la bioeconomía en la provincia de Misiones. Buenos Aires, Consejo Federal de Inversiones.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) (2003). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: a Framework for Assessment. Millennium. Ecosystem Assessment. Island Press, Washington, D.C. EE.UU.

Ministerio de Hacienda y Finanzas Públicas Presidencia de la Nación (2016). Informes de cadenas de valor: forestal, papel y muebles.

Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Productiva (2013). Núcleo socio-productivo estratégico: producción y procesamiento de recursos forestales.

Mthembu, L. D., Gupta, R. y Deenadayalu, N. (2021). Conversion of cellulose into value-added products. Cellulose Science and Derivatives.

O’Farrell, J., Stubrin, L., Freytes, C., Bortz, G., Mendoza, F. A. y Cappelletti, L. (2023). El rol de la bioeconomía en el desarrollo productivo regional: aprendizajes y desafíos con base en un estudio del biocluster de Rosario-Santa Fe. Fundar.

Rodríguez, A. G., Rodrigues, M. D. S. y Sotomayor Echenique, O. (2019). Towards a sustainable bioeconomy in Latin America and the Caribbean: Elements for a regional vision. CEPAL.

Salzman J., Bennett G., Carroll N., Goldstein A. y Jenkins M. (2018). The global status and trends of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Nature Sustainability.

Starobinsky, G., Monzón, J., Di Marzo Broggi, E. y Braude, E. (2021). Bioinsumos para la agricultura que demandan esfuerzos de investigación y desarrollo. Capacidades existentes y estrategia de política pública para impulsar su desarrollo en Argentina. Documentos de Trabajo del CCE N° 17. Consejo para el Cambio Estructural – Ministerio de Desarrollo Productivo de la Nación.

Verkerk, P. J., Hassegawa, M., Van Brusselen, J., Cramm, M., Chen, X., Imparato Maximo, Y. y Koç, M. (2021). Forest products in the global bioeconomy: Enabling substitution by wood-based products and contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals. FAO.

Wunder S., Wertz-Kanounnikoff S. y Moreno-Sanchez R. (2007). Pago por servicios ambientales: una nueva forma de conservar la biodiversidad. Gaceta Ecológica número especial 84-85 (2007): 39-52 D.R. Instituto Nacional de Ecología, México.

OECD. (2021). Tracking economic instruments and finance for biodiversity.

Notes

1. The Nagoya Protocol is an international agreement that regulates access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilisation. The purpose of the agreement is to ensure that access to genetic resources and benefit-sharing (ABS) is carried out in a balanced, legal and ethical manner, respecting the rights of provider countries and local communities that have traditionally used and conserved such resources.

2. Bioinformatics refers to the use of computer science to collect, store and analyse data and information from biological resources, such as DNA sequences. Omics’ is a term used to refer to the study of the whole or the whole of something, such as genes, organisms in an ecosystem, proteins or even the relationships between them.

3. This is the most advanced project for the installation of the first second-generation biorefinery for the production of chemical inputs integrated by four institutions of the national innovation system with a presence in the region: CONICET, INTI, UNaM and UNT. BioNA proposes the construction of two pilot plants for the manufacture of products, materials and energy from biological resources, to be located in the provinces of Misiones and Tucumán.

4. Estimates by Salzman et al. (2018) identified more than 550 PES programmes worldwide and an estimated USD 36-42 billion in annual transactions.

5. This type of coating can reflect incident solar radiation while emitting thermal energy in the infrared. In other words, they have high solar reflectance and high thermal emissivity. The pilot test was carried out in the neighbourhood of Itaembe Guazú by the Reno startup from Reno Nevada, USA, to which the provincial government provided a warehouse in the Industrial Park of Posadas. Teams from the Ministry of Climate Change, the University of Nevada, Reno and the University of Los Angeles (UCLA) are working on the development of this methodology.

REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) projects refer to a mechanism for financially rewarding developing countries for their achievements in avoiding greenhouse gas emissions associated with deforestation and forest degradation. The “+” in the acronym is to recognise other efforts to maintain the forest, such as sustainable forest management, conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks. In this sense, PES schemes are part of initiatives aligned with REDD+ objectives by providing economic incentives to landowners to conserve forest areas and thus not emit greenhouse gases.

Citation

Mendoza, F., Villafañe, M. F., O’Farrel, J. (2024). Misiones posible: desarrollo económico y conservación de la naturaleza. Fundar.