The socio-economic situation of recent years in Argentina has put the food issue at the centre of the agenda and the difficulty for a large part of the population to satisfy the most basic needs. In this context, we need food policies that guarantee physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food.

Illustration: Brenda Ruseler.

Throughout this year (2024), the public agenda in Argentina has been marked by different debates about how the state intervenes in the living conditions of the population and, in particular, in that of the most vulnerable segments of the population. In the field of social policy, this year’s debates focused on employment programmes, socio-urban integration policies in poor neighbourhoods, and food policies, particularly about the purchase and distribution of food.

A frame of reference: destitution in Argentina

The backdrop against which the current discussion on food policy is taking place is the evolution of indigence in our country, also known as extreme poverty. This indicator is the percentage of people living in households whose income is insufficient to purchase a Basic Food Basket (CBA). It is a measure that approximates the food situation of the population, although it is indirect: it does not measure effective access to food but rather the purchasing capacity of households.

Indigence in Argentina has been growing since 2018, in a context of high inflation (figure 1). In the first quarter of 2024, indigence jumped from 13.8% to 20.3%.

Current levels of indigence indicate that economic access to food for the vulnerable population is the priority food problem in Argentina. Moreover, the figures reveal that achieving improved nutrition will require supporting families in accessing a healthy food basket.

What do indigent households look like?

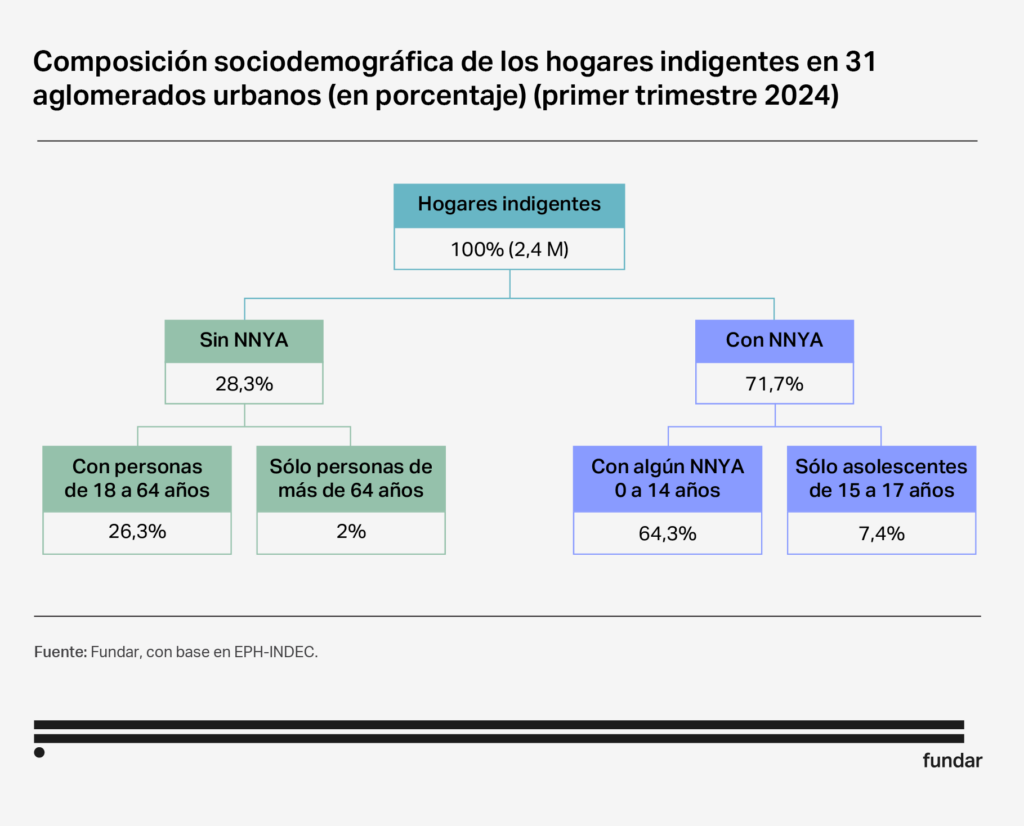

Indigence, within the 7 million poor households in Argentina, currently affects households with children and adolescents (NNYA) most intensely. In 71.7 per cent of destitute households there are children aged 0-14, which can be translated as a more extreme form of the well-known “infantilisation of poverty”. Within the remaining 28.3% of destitute households (without children) there are mostly people of economically active age (Figure 2).

Existing policies to address the food issue

Food policies deployed by the national state and sub-national jurisdictions (provincial and local) seek to ensure access to food for vulnerable families. If we focus on the national State, it is possible to differentiate three intervention formats:- Food cards are aimed at individuals or families in critical or socio-economically vulnerable situations.

- Direct food assistance (DFA): Includes both benefits in kind (food modules) and economic transfers to canteens, soup kitchens and social and community organisations for the delivery of food rations.

- Support for food production and marketing, aimed at sectors of the social, cooperative and popular economy, through the promotion of family farming, fairs and local markets.

According to the provisional data available, in the first months of Javier Milei’s government, some changes are taking place in terms of how the food issue is managed. On the one hand, real spending on food cards was reduced (-6%) and much more sharply on DDA (-65%), which led to a change in the composition of food spending.

This reduction in DFA spending by the government, in a supposed quest to “disintermediate” food assistance, has negatively affected the provision of food kitchens and street food kitchens. On the other hand, the government is increasing spending on AUH, which grew by almost 50% in real terms, making it the main cash transfer in the context of an adjustment of the other spending components.

The Alimentar Benefit

Since 2019, the Argentine State implemented a wide-ranging income transfer food policy associated with the universe of AUH beneficiaries, called Tarjeta Alimentar (currently Prestación Alimentar). In its original design, it targeted families with children up to 6 years old who were beneficiaries of the AUH and families benefiting from the Pensión por 7 Hijos. During the pandemic, the amount of Alimentar was transferred to the same account in which the AUH was deposited. The programme now functions as a complement to the AUH with no restrictions on its use. As of the first quarter of 2021, the programme will also cover AUH beneficiary families with children up to 14 years of age.

According to the analysis presented in our paper, the Alimentar Benefit has at least five design problems:

- It excludes adolescents (NNYA) between 15 and 17 years old. The current design arbitrarily excludes a certain profile of households according to their composition. Households with children under 15-17 years of age represent 7.4% of indigent households. This design also generates a negative income shock for families when one of the children and adolescents has a birthday and is excluded from the calculation for the payment of the transfer.

- At present, the sum of the AUH and Alimentar transfers is not enough to cover the indigence line per adult equivalent.

- The same protective system, aimed at the same target population (households with children and adolescents in vulnerable situations), offers differential and decreasing amounts depending on the number of children and adolescents in the household, without it being clear why this scheme is justified.

- While the amount of the AUH has been adjusted according to pension mobility, the Alimentacion Alimentar benefit has no pre-established updating criteria.

- Lower-income formal workers do not receive any allowance comparable to the Alimentar benefit. In the low-income segments of the family income bracket, this can generate a difference to the detriment of formal workers. The decoupling of AUH and AFH has aggravated this situation.

Some guidelines for strengthening food policy

The following are some guidelines for strengthening the national state’s food policy in the context of increasing indigence, but also with a longer-term orientation to build minimum levels of well-being.

- Prioritise cash transfers over in-kind transfers: The national state should prioritise cash transfers over in-kind transfers, based on principles of efficiency and transparency. Cash transfers have lower implementation costs, are more transparent and give greater choice in deciding what to buy and how to eat.

- Unify transfers per child: expand Alimentar and cover the Basic Food Basket. We propose unifying the coverage of the Alimentar Benefit with the transfer criteria of the AUH. This implies reaching the entire universe from 0 to 17 years of age and that the sum of both benefits should be equivalent to the Basic Food Basket (CBA). Likewise, the CBA constitutes a general reference criterion for updates, taking into account regional disparities in purchasing power.

- Move towards greater protection to avoid disincentives to formality. The social protection system must have a virtuous articulation with the dynamics of the labour market. In the context of falling wages, the current design generates inequity at the lower end of the wage scale and excludes a population of children and adolescents living in households with adverse economic situations. For the lower formal wage brackets, the amount of family allowances should be brought into line with the amount received by AUH and Alimentar recipients.

- Prioritise local management of direct food assistance. This is key to avoiding the overlapping of assistance by different levels of government and for the different jurisdictions to take on different axes of food policy corresponding to their specific problems. Local governments have a greater capacity to detect critical situations of vulnerability that require direct assistance. Finally, local management reduces the operational intermediation costs associated with centralised food procurement and ensures better adaptation to local food habits and customs.

- Promote the nutrition education component. Healthy eating is a contributory condition for the prevention of chronic diseases with important aggregate social effects. Increasing the presence of foods that provide essential nutrients, reducing foods of low nutritional quality and adequate intake of calories according to the requirement, imply the improvement of nutritional quality.