The path to become a judge in Argentina would seem to be the same for everyone. After all, it is a neutral and meritocratic procedure. The issue is that it hides the structural inequalities that women face every day. How to make this glass ceiling visible? A study on the selection processes of male and female judges.

Illustration: Natalia Aguerre

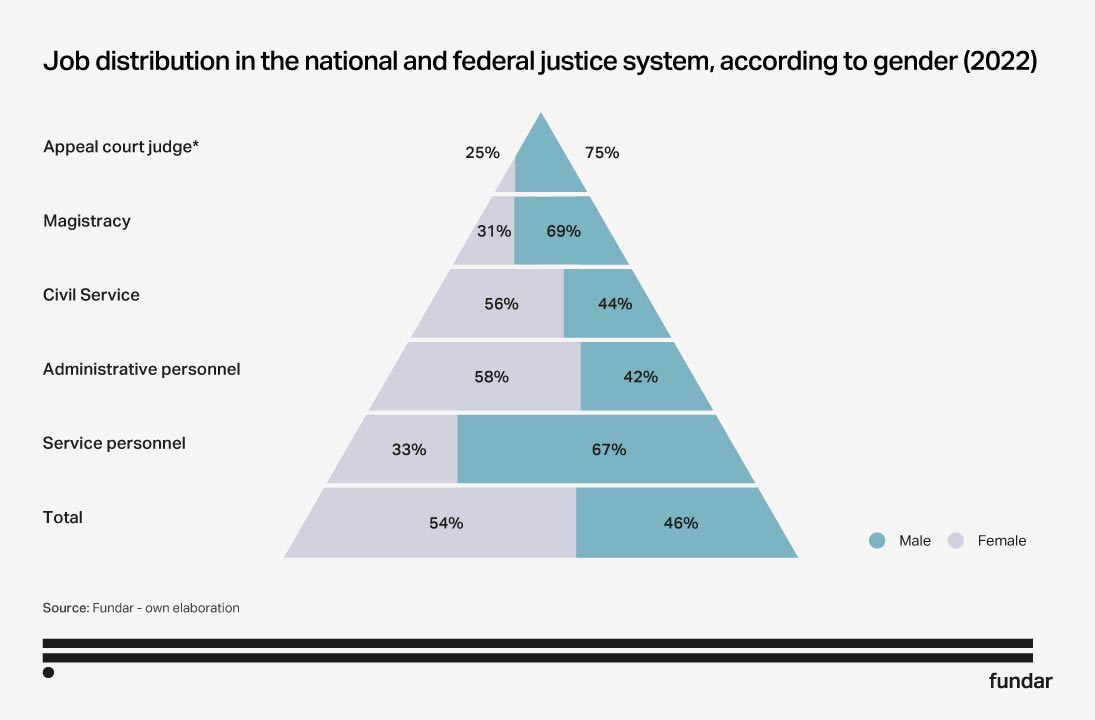

Women account for 54% of the Argentine judiciary, but only 25% of the highest positions. Although women generally have higher qualifications, only 23% of candidates for a judge position are women. Invisible barriers discourage them from competing for higher decision-making and hierarchical positions. This analysis focuses on the selection and appointment processes of the Judicial Council in an attempt to unveil the workings of this “glass ceiling” in Argentina’s judicial system.

Candidates to fill these hierarchical positions are selected by competition, a selection process neutral and meritocratic at first glance. A close-up, however, reveals that the path is different for men and women. Until now, the lack of systematized data prevented us from evaluating it and understanding how it affected women’s access to the bench. For that reason, we built an unprecedented database with information of competitions convened from 1999 to 2018.

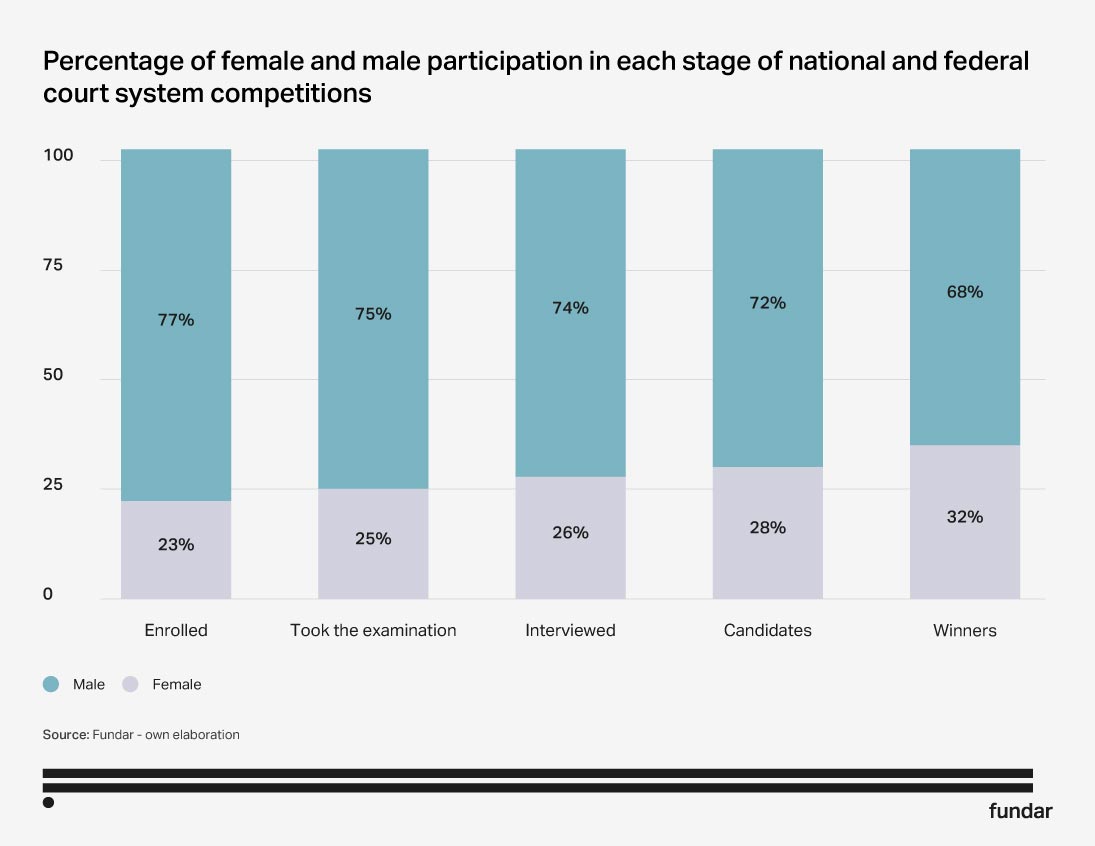

The empirical evidence quickly reveals a first major barrier: enrollment. Only 23% of candidates are women. However, women who do apply obtain higher scores than their male counterparts. As a result, the percentage of women applicants increases at each step. The question arises, why are there so few women applying?

This paper analyzes the selection processes of male and female judges of the Judicial Council and explores a key problem that affects the functioning of the Argentine judicial system: the low percentage of women in the competitions and the impediments that prevent them from occupying higher positions, known as the “glass ceiling”.

A gender map of Argentina’s judiciary

A quick look at the gender composition of the Argentine judicial system reveals that women account for more than half of court officers and public servants within the judiciary. They make up 54% of the total staff, 58% of the administrative staff and 56% of officers, but only 25% of the highest positions, Justices, Attorneys General and Public Defenders General. This situation has remained practically unchanged over the last 20 years. What potential factors might help explain this flagrant underrepresentation of women in higher roles?

The process for the selection of judges involves several stages and lasts no less than a year. There have even been competitions that lasted over six years. Although the selection process for male and female judges is presented as a neutral and meritocratic process, its characteristics have a differential impact on women and men.

In an attempt to identify the reasons for this disparity, we built an unpublished database with information from all competitions held from 1999 to 2018. We analyzed the information provided by the 3963 applicants to the 104 competitions held to fill 226 appellate judge vacancies. This database provided data on the number of applicants at each stage, including their age and gender, their scores and assessment across the different stages, the relationship between age and score, and the evolution of women’s participation along the 20-year period of competitions analyzed.

Unveiling the glass ceiling

One of the most revealing findings shows that on average only 23% of the people participating in these competitions are women, a figure that has remained relatively stable over the 20 years analyzed, despite progress achieved in gender equality during the same period. However, once they enroll, women advance with better results than men in the successive stages of the competitions. The percentage of female participation increases at each stage: from an initial 23% to 32% in the final stage.

What is the reason for this increased participation? One possible explanation could be found in the fact that women obtain higher scores throughout the different stages (both in public exams and merit-based assessments). Another factor that influences the selection process is age. Female candidates are older than their male counterparts: women who successfully navigate the selection process have an average age of 54, while successful male applicants have an average age of 51.

May the best man/woman win?

The low enrollment of women, the age factor and the average scores obtained are crucial in highlighting the unequal experiences between male and female contestants. To understand these disparities, we have focused on three dimensions:

- The lack of gender perspective of the judge selection regulations.

- The attempt to balance family life and career.

- High self-expectations in the competition.

The competitions were designed with the male experience in mind and are blind to the circumstances faced by women. They overvalue aspects such as academic production, writing books or articles, or access to training and specialization courses, over merit and capacity as shown in judicial resolutions.

“Once included on the [parity] lists we all participate in the same merit and theoretical competition, through oral interventions, written tests and so on, [but] attention must be drawn to the design of these competitions, because they are often based on standards thought for men only. For example, although the number of publications may come across as an objective criterion, women are sometimes unable to publish because of motherhood. In my view, competition criteria are often blind to these different circumstances. While objective on the surface, the analysis falls short in addressing women's specific circumstances.”

Testimony of a female judge candidate, Núcleo de Estudios Interdisciplinarios, 2022

The answers to some of these questions can be found in the articulation between the conduct of women in the judicial labor sphere and the domestic space, where they bear the lion’s share of the care burden. The problem of the “glass ceiling” in the Judiciary cannot be considered in isolation, but in the context of the tensions between career and family life and the differential impact of such tensions on men and women, to the detriment of the latter.

To the social barriers discussed above add also self-imposed barriers. The levels of self-confidence and self-esteem also have a differential impact on men and women. Those women who advance through the stages of the competition match the performance of their male counterparts or even outperform them, meeting or exceeding applicable requirements. Nonetheless, women imply higher demands from a hierarchical judicial position than their male counterparts, which discourages them from applying, and eventually obtaining such offices.

Towards a more inclusive selection process

In light of the deeply-rooted disparity described above, women are not on an equal footing with their male counterparts. This highlights that the selection process for male and female judges is not egalitarian, discourages women’s participation in competitions and reinforces the prevailing glass ceiling.

The paper concludes with the following recommendations to improve public policy in the selection processes:

- Promote regulatory modifications to account for the different social and cultural barriers faced by women in merit-based selection processes.

- Establish a gender quota —as vacancies arise— to ensure equal representation of men and women in the court system. This will also encourage greater enrollment by women.

- Give greater relative weight in the final score to competitive examinations than to merit-based assessments, since it has been established that young people and women tend to perform better at exams.

- Produce constant and updated empirical evidence to monitor the data and evaluate whether or not the number of women enrolled in competitive examinations changes over time.

- Promote awareness and outreach campaigns to encourage women to apply for competitive examinations.

- Design a gender-sensitive budgetary policy for competitions, allocating specific resources for their planning, development and evaluation.