The energy transition is driving unprecedented demand for minerals, including lithium. Argentina, with 13.3% of global reserves and a growing number of projects underway, could play a central role in supplying this strategic commodity.

This opportunity poses a key challenge: how to ensure a tax framework for the development of lithium mining that distributes benefits equitably, strengthens state capacities, and guarantees the development of producing regions. An analysis of the current regime, the RIGI, a financial model, and a proposal for reform. A future tax on lithium.

The current situation

- The tax regime for lithium mining currently in force in Argentina is characterised by its regressivity, instability and poor coordination between levels of government. Based on a financial model that simulates the long-term fiscal impact under different price scenarios, we conclude that:

- The current system could result in annual losses of between USD 157 million and USD 378 million compared to more efficient schemes.

- The country has room to improve its effective tax rate without affecting investment.

The current tax system favours national revenue collection, relegating the provinces that are the original owners of the resource, which receive royalties and a portion of certain national taxes through revenue sharing.

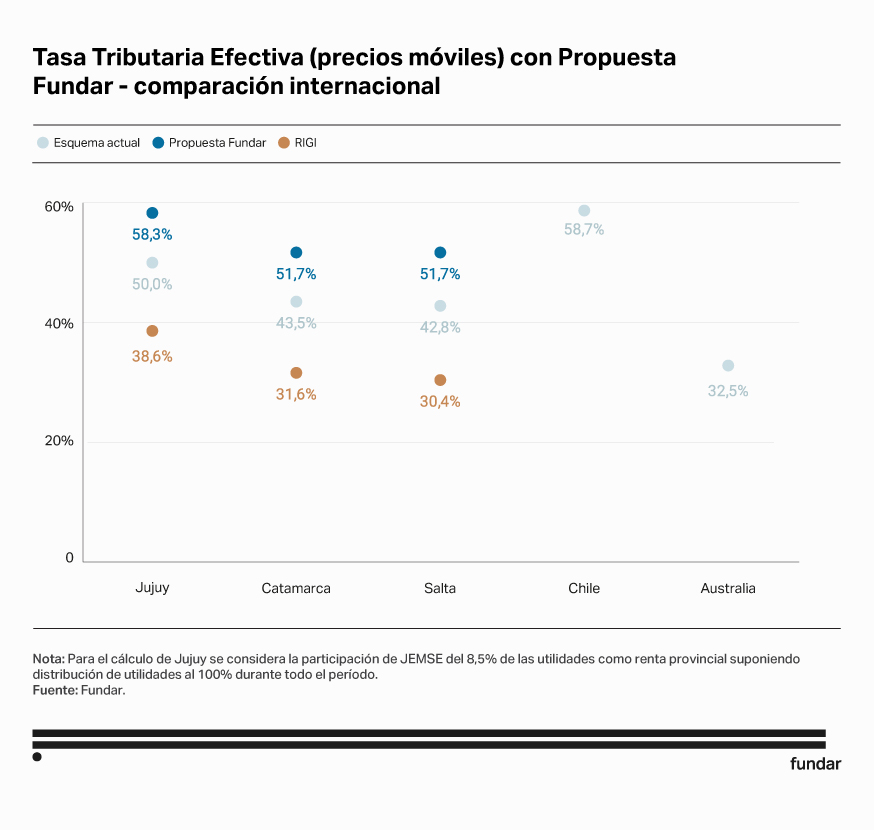

The Large Investment Incentive Scheme (RIGI) reduces the effective tax rate. For example, for a project based in Salta, the effective tax rate drops from 42.8% to 30.4%. According to our model, for a typical 40,000 t LCE project, the revenue losses over 40 years of operation due to the introduction of the new regime could total USD 2.382 billion compared to the current scheme and USD 4.237 billion compared to the proposed progressive scheme.

Furthermore, institutional fragmentation between the national government and the lithium-producing provinces of Catamarca, Salta, and Jujuy—with agencies that collect and oversee different taxes at both levels of government—leads to efficiency losses and doubles costs.

International comparison

To analyse the effects of price cycles on tax revenue, two estimates of the Effective Tax Rate (ETR) are presented:

- assuming a fixed price of USD 12,000;

- simulating a moving price.

The table also shows:

- the variation in TTE between both scenarios

- the elasticities of the effective tax rate in response to changes in the international price. The latter estimates how much the tax burden varies in response to a 10% change in the international price of lithium carbonate.

Simulation of effective rates according to fixed or variable prices

| Price | Argentina | Chile | Australia | |||

| Jujuy | Catamarca | Salta | RIGI (Skip LB*) | |||

| (1) Fixed (flat) USD 12,000 |

54,0% | 48,0% | 47,0% | 33,4% | 57,4% | 36,7% |

| (2) Mobile | 50,0% | 43,5% | 42,8% | 30,4% | 58,7% | 32,5% |

| (3) Variation | -7,4% | -9,4% | -8,9% | -8,9% | 2,3% | -11,4% |

| (4) Elasticity | -0,20 | -0,25 | -0,24 | -0,97 | 0,06 | -0,28 |

Source: Fundar.

Note: Mobile: base USD 12,000 plus a random shock with normal distribution with mean zero and standard deviation USD 25,503.54. Elasticity was calculated with a 10% fixed price increase from USD 12,000 to USD 13,200. *Salta LB, Law Bases is taken as the base case for future projects adhering to the RIGI where the royalty rises from 3% to 5% “at the mine mouth” in accordance with Article 103 of Law No. 27,743 to which the province adhered in 2024 through Law DGR 8,448.

What do the estimation results show? First, Argentina’s tax burden is, on average, almost 10 points lower than that of Chile, a country with similar production costs. In the case of Jujuy, this difference is reduced to 3.5 points due to the provincial company JEMSE’s share of profits.

Furthermore, the RIGI significantly widens the tax gap with Chile. A project adhering to the RIGI would have a tax burden in the province of Salta between 24 and 28 points lower than in Chile (depending on whether the fixed price or sliding price model is considered). This difference remains even assuming a scenario of an increase in royalties to 5%.

With these results, Argentina has potential scope to increase the effective tax burden without risking losing competitiveness vis-à-vis Chile, the main producer in the lithium triangle. The RIGI went in the opposite direction and, by including lithium mining, unnecessarily increased the tax gap between Argentina and Chile. The only exception was to include the possibility of increasing the royalty cap from 3% to 5% ––at the mine mouth–– in the Basic Law, which has only been legislated to date by the provinces of Catamarca and Salta.

Secondly, the Argentine tax system is characterised by its regressivity, that is, its inability to capture higher tax revenues in the face of a cycle of rising prices. This characteristic can be seen in the comparison of the TTE between the fixed price scenario (1) and the mobile price scenario (2). For a lithium project located in Salta or Catamarca, tax revenue collection decreases in a mobile price scenario, on average, by around 9%. The elasticity dimension supports the same conclusion.

The RIGI deepens fiscal regressivity by reducing the most progressive tax rate, the IIGG: for a project adhering to the regime, a 10% increase in the price of lithium translates into a drop of almost ten points in the TTE.

Public policy recommendations

- Implement a single, hybrid, progressive mining tax that combines an ad valorem component (fixed royalty of 1.5% on the sale value), a variable component based on international lithium prices, and another variable component based on operating margins. This scheme offers greater predictability to investors and guarantees stable revenues for the State; it allows for the capture of extraordinary income during high price cycles and guarantees a lower tax burden on investors when prices decline.

- Unify tax bases and audit criteria. The simplified regime enables the unification of the tax base and audit criteria between ARCA/Customs and provincial agencies, minimising the risks of tax base erosion and profit shifting and reducing compliance costs. The establishment of formal channels for information exchange and joint control operations would generate economies of scale, cross-checks and efficiency improvements in tax administrations.

- Review and index the water levy to internalise the water externalities of lithium extraction (from 0.06–0.09 USD/m³ to a range of 0.50–1 USD/m³). Adjusting this levy creates incentives for the incorporation of more efficient recovery technologies and improves the sustainability of high Andean ecosystems. The rate increase must be accompanied by an indexation mechanism.

- Incorporate the small and medium-scale perspective. Finally, instruments such as the RIGI are geared towards large-scale investments, but in Argentina and around the world there are also scalable projects that are generally excluded from the tax design, which tends to focus on large taxpayers and neglect intrasectoral heterogeneity. It is proposed to use the model to evaluate the fine calibration of the proposed regime in order to incorporate projects located in less favourable cost quartiles or, alternatively, to evaluate a differential instrument for small and medium-sized projects (as has been done with the IEAM in Chile), so as not to discourage such developments.