Big data goes a long way to gain knowledge about the population. Its volume and granularity enable conclusions often overlooked in traditional sources (polls, interviews or official records). Although commonly used for customer segmentation, its potential for understanding the population targeted by public policies remains untapped. This paper explores, specifically from the perspective of the Federal Ministry of Tourism and Sports, the potential of these alternative data sources for improving the design and implementation of public policies.

Illustration: Noe Garin

Big data for public policy-making

The State requires information for decision-making, effective public policy design and impact assessment. It needs data on the population targeted by these policies and the context in which they are to be implemented. In this sense, the information available at state level is usually imperfect and inadequate. However, the use of alternative sources of information is not a common practice for the public administration.

Can big data coexist with traditional sources and add to the information readily available to find those the state engages or speaks with? This paper presents a joint experience between Fundar, the National Directorate of Markets and Statistics of the Federal Ministry of Tourism and Sports and the Laboratory of Discrete Event Simulation of the School of Exact and Natural Sciences, University of Buenos Aires. It seeks to improve analysis and understanding of domestic tourism flows and to provide new information on tourism markets for the implementation of public policies in the sector.

Traditional sources / alternative sources

The Federal Ministry of Tourism and Sports has several information-gathering tools. These include the Federal Tourism Data Management System of Argentina, the Household Travel and Tourism Survey (EVyTH) and the Hotel Occupancy Survey (EOH). However, these sources do not provide all the information needed. For this reason, we considered supplementing them with another source, in particular one that would provide geographic and temporal disaggregation.

The secondary source used is a georeferenced database that collects data from mobile devices. It offers information on the point of origin of trips made throughout the national territory, with daily temporal granularity and a breakdown by destination. In this way, it provides those involved in the tourism industry with more detailed information on the origin and destination of trips, thus enabling an analysis of the routes taken to get from one point to another.

Big data methodology

The starting point of the process is a database containing anonymous information from mobile devices that are identified using a unique advertising code or IFA (Identifier for Advertising). Each of these IFAs is assumed to be an individual. Since the information is anonymous, this data provides an overview of the characteristics of the local population, without the possibility of associating this record to any particular individual.

The database contains daily georeferenced records, from April 2019 to March 2020, from the 528 departments, districts and communes of the 23 provinces and the Federal Capital of Argentina (except Antarctica and South Atlantic islands).

Each IFA (or unique user) was assigned a place of residence, which was identified based on the most common georeferenced evening location (CEL). This geographic coordinate also allows each IFA to be linked to a set of socioeconomic characteristics associated with that residential area. Their trips were also analyzed, assuming a trip is for tourism if the IFA is found at a certain minimum distance from the place of residence (40 km for the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires and 20 km for the rest of the country).

Monthly trip comparison

A first exercise was to compare the data obtained from primary and secondary sources on the trips made each month. As in the EVyTH design, this was done by filtering the data provided by the secondary source for trips with the same origin (i.e. from one of the large urban agglomerations) and destination within specific requirements in terms of distance traveled and traveler´s usual environment during the same reference period (April 2019 – March 2020).

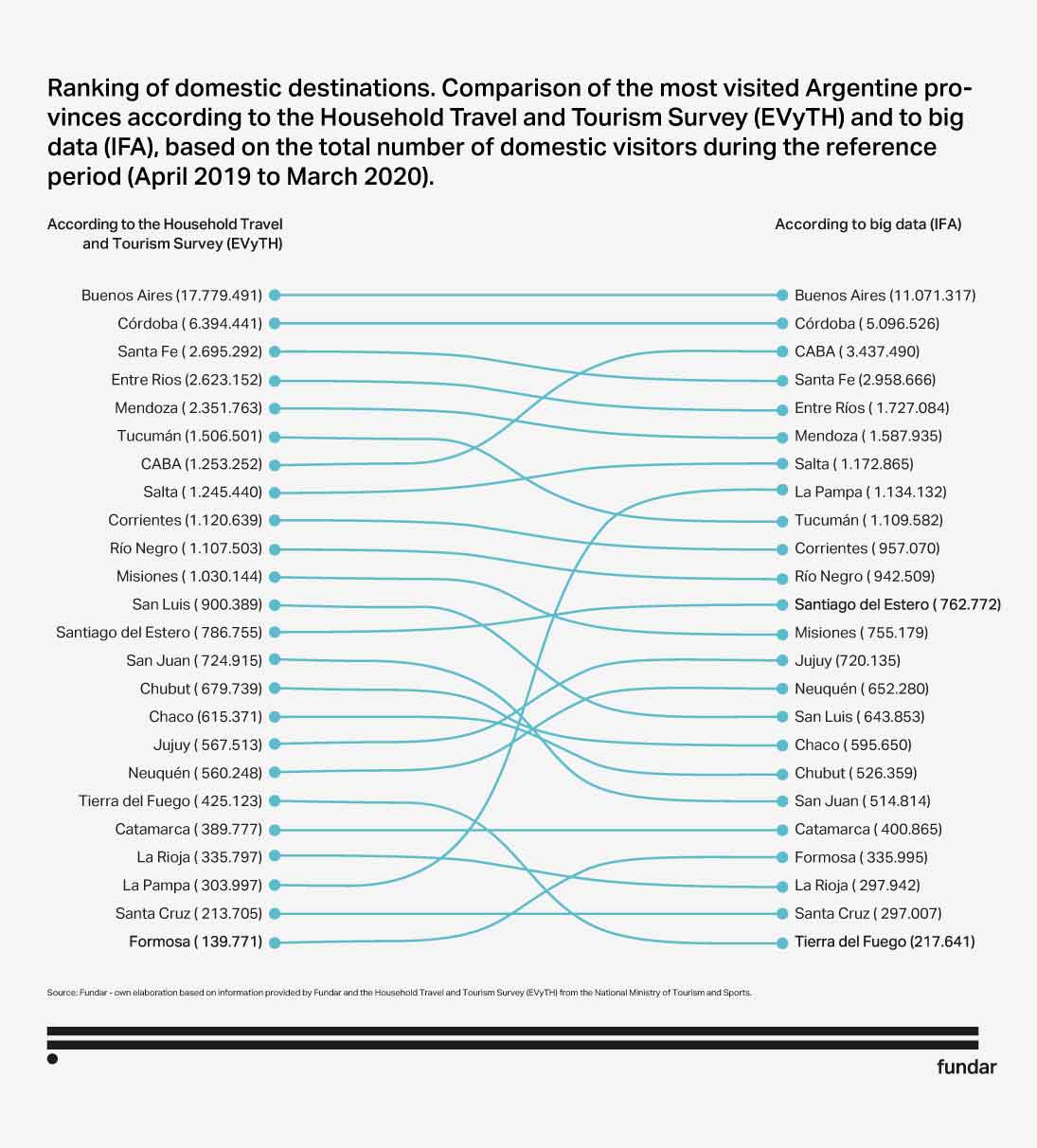

Comparison of most visited tourist destinations

A second exercise involved comparing data on the most visited destinations. Although the ranking of destinations by province shows relatively similar results, there are some salient differences for districts such as the City of Buenos Aires (CABA), La Pampa and Río Negro. In all fairness, that difference could potentially be due to a more accurate reflection, given that the EVyTH inquires as to the main destination of a trip, while IFAs record a geographic location at a given point in time. The fact that La Pampa ranks much higher when using big data than when analyzing the survey findings is consistent with the fact that it is a common stopover in trips with final destination in different cities of Patagonia, for instance.

Big data in tourism: two case studies

The use of alternative data sources allows other avenues of analysis to overcome some of the limitations inherent in survey design. Surveys provide aggregate information by tourism region, broken down by quarters, and are generally designed to record visitors’ origin. Conversely, georeferenced data from mobile devices provides an opportunity to explore origin information at department or census tract level, with daily temporal granularity, broken down by trip destination.

Nature tourism: Iguazú National Park

Natural tourism is a strategic niche for Argentina’s tourism industry, and it is one of the fastest growing in the country and abroad. This growth may be explained by a global trend that reflects the desire on the part of an increasingly urban population to reconnect with nature, and these tourist destinations are undoubtedly among travelers’ favorites. The COVID-19 pandemic has only been a catalyst for this trend.

A relevant source of information for tracking behavior related to nature tourism comes from the National Parks Administration (Administración de Parques Nacionales, or APN), which records park entrance data. It provides information on the number of visitors to each park and whether or not they are national residents.

With these alternative sources, we can supplement the information to build profiles of visitors to the National Parks. For example, let us analyze the most visited National Park: Iguazu Falls. We filtered from the database those IFAs that were present within the boundaries of this protected area.

Number of visitors

The monthly data were then compared with the number of visits recorded in administrative records. Despite some discrepancies between source estimates, month-to-month variations depict a similar behavior.

Origin of visitors

The determination of the habitual residence (based on the CEL) provides insight into the origin of visitors (either at the provincial or departmental level) and their socioeconomic level. For example, we can see the provinces of origin of those visiting Iguazú, and even drill down to find the district of origin.

Socioeconomic level of visitors

In terms of socioeconomic profile, we see a higher proportion of visitors with a medium-high socioeconomic level (NSE +1, +2, +3) according to IFA records.

Festival tourism: the Gualeguaychú Carnival

The Ministry of Tourism and Sports also keeps a register of national festivals, with approximate dates (they may vary from year to year) and a characterization of the type of activities they feature. Unlike the analysis of domestic tourism in general and the comparison with the EVyTH, or the comparison of National Parks visitors against data obtained from administrative records, we do not have analogous information for this type of event. No accurate information on visitors to this type of event is available. However, there are other sources we can use as an approximation for the purposes of our analysis.

Number of visitors

In Argentina, carnival celebrations take place during the weekends of January and February, culminating with the “Carnival National Holiday”. The visitor profile has been derived from the IFAs identified on these dates, within 3 km from the city of Gualeguaychú.

The choice of Gualeguaychú as an example for the Festival Tourism use case is not arbitrary. First, it is one of the festivals for which the largest number of records is available. Secondly, festivals can be ranked based on the number of departments of origin (address), as shown in the table below, and since the city is included in the Hotel Occupancy Survey (HOS), it is then possible to compare the behavior shown in this new data source with the available statistics.

Origin of visitors

Once again, the exercise of identifying the IFAs of those who attended the Carnival Festival allows us to characterize its visitors. By quantifying the participation not only by provinces of origin —as recorded by the EOH— but with a greater disaggregation down to census tracts, we can then observe socioeconomic differences and evaluate profiles.

Socioeconomic level of visitors

The lack of data affects public policy design, public decision-making and policy impact evaluation. The use of alternative sources of information to supplement traditional databases offers a way to improve the information available for decision making. This paper shows a method that draws on alternative data sources along with already known information used as a pivot. The use cases served to validate the quality of the information obtained in the surveys and supplement it. The method developed can be replicated and applied to analogous cases. It can algo be used to obtain information not previously available from existing sources of information.