Despite limiting the productive performance of the agricultural sector and having an ambivalent distributive impact, export duties have been maintained throughout the different terms of office. Why were they maintained for so long when other tax instruments are more virtuous in productive and distributive terms? This is largely due to the difficulty of substituting the revenues they generate. This paper discusses the fiscal, productive and distributive effects of withholding taxes, describes the panorama of the use of these taxes in the world, and proposes a new fiscal framework for Argentine agriculture.

Illustration: Pint0rcito

Discussing export duties: towards a new fiscal framework for agriculture

What are export duties?

Comúnmente llamados “retenciones”, los derechos de exportación (DEX) son tributos aplicados en la aduana que gravan la venta al exterior de distintos bienes (como el trigo, el maíz, el poroto de soja y sus derivados), tomando como base imponible las cantidades declaradas al precio internacional vigente. Su importe se obtiene mediante la aplicación de un porcentual sobre el valor de la mercadería.

Who is affected by export duties?

Although the person legally obliged to pay the tax is the individual or legal entity that sells the goods abroad, withholding taxes mainly affects local producers. This is because exporting companies transfer the cost of the tax to the price they pay to the producers, and these end up being the ones who are affected.

How do export duties arise?

Withholding taxes have a long history: there are records of their appearance around 1850. They were reestablished in 2002 as a way to obtain part of the extraordinary income generated by the devaluation of the agro-export sector and to compensate for its impact on the population.

Except for the interval between December 2015 and September 2018, they have remained in force beyond the international commodity prices and the level of the real exchange rate. And they have transcended governments of different partisan signs, programmatic orientations and territorial anchorage.

Objectives and effects of export duties

Beyond the differences that may occur in the different periods (either in the rates, in the products taxed or in the additional restrictions), the reasons for using this instrument have remained constant. Export duties have mainly had collection, distributive and productive objectives.

Collection objectives: a tax with great revenue-raising power

Withholding taxes allow the national government to regularly collect and capture part of the extraordinary income received by the producer in devaluation contexts. This objective is effectively achieved: DEX have become a pillar of the Argentine tax structure. In the last two decades, they accounted, on average, for 5.5% of annual revenues. And, in 2022, they were the fourth national tax with the highest share of total revenues after VAT (23.9%), Income Tax (19.3%) and social security contributions (17.7%).

Distributional objectives: a tax with ambivalent redistributive effects

Another objective of this measure is the redistribution of income from the agro-export sector to other sectors of the population. This occurs through two channels: the price of foodstuffs and the progressiveness of the tax burden. Both objectives are only partially met.

On the one hand, withholding taxes seek to lessen the impact of international price increases on domestic market prices. Even if they manage to decouple the local price of primary products, their effect on the final price of food is low (given that raw materials represent a minor part in the formation of the final price of consumer goods).

On the other hand, export duties seek to redirect resources from high-income sectors (such as agricultural producers) to lower-income sectors, through taxation and public spending. Even if they tend to fall on higher income sectors, they tax the gross sales value without taking into account the cost structure of producers with different realities. This penalizes farms farther away from the port and from the area with the highest agricultural productivity.

Productive objectives: a tax with a negative effect on production

Withholding taxes were created to balance Argentina’s productive structure: channelling resources from the agricultural sector (highly productive but supposedly with low value-added, little innovation and little capacity to generate employment) to the manufacturing sector.

However, these theories omit the transformations in the productive structure of agriculture, which has incorporated technology, developed industrial links and generated an industry supplying goods and services.

DEX generate a disincentive to the production and export of the taxed goods, to the extent that they reduce the price received by the producer and his margin of profitability.

This may even end up affecting the production of goods that use those primary goods as inputs since their supply is reduced. In addition, they negatively affect technology adoption, since lower profitability reduces the accumulation of capital available for investment.

What would happen if export duties were reduced?

Given the negative effects on production and investment, in recent years there have been proposals to reduce or eliminate export duties. What effects could such proposals have?

To answer this question we can look at what happened the last time agricultural withholding taxes were reduced in December 2015. Based on that information, we estimate what would have happened if there had been no change. The comparison between what happened (scenario with DEX reduction) and this counterfactual scenario (without DEX reduction) allows us to measure the impact of withholding taxes.

According to the results of this estimation exercise, the decrease in export duties had a positive impact on the sector’s investment (measured through fertilizer consumption) compared to what would have happened if they had remained unchanged.

As for the impact on production, the effect of the decrease in the soybean withholding tax rate, from 35% to 30%, on production was negative. This result is contrary to expectations since an increase in the perceived value would be expected to lead to an increase in production.

This makes sense when we look at what happened to substitute crops, such as corn, whose tax rate was reduced from 20% to 0%. This differentiated reduction encouraged a change in land use (from soybean to corn), promoting a greater rotation between crops. The impact on wheat production was notoriously positive: in the 2016/2017 season, after the reduction of the aliquot, production was 35.4% higher than it would have been if it had not been modified.

What are other countries doing? A review of international experience

Argentina is not the only country that has used export taxes to contain domestic food prices in the face of rising commodity prices. However, it differs from the rest of the countries in scope and magnitude.

Globally, out of a sample of one hundred and sixteen countries, thirty-eight levied export taxes in 2020. But that number is reduced to five if we consider only those in which export tax collection on GDP was greater than 0.5%. These five countries are Russia (1% of GDP), Kazakhstan (1%), Ivory Coast (1.2%), Argentina (1.4%) and Solomon Islands (3.7%).

Argentina also stands out as one of the countries that provides the least support to agricultural producers. Except for India and, to a lesser extent, Ukraine, all the main wheat, corn and/or soybean exporting countries show positive values, while Argentina has always obtained zero or negative values. This means that even though most countries provide support to agricultural producers, in Argentina agricultural producers transfer resources to the State and subsidize domestic consumption.

Towards a new fiscal framework for agriculture

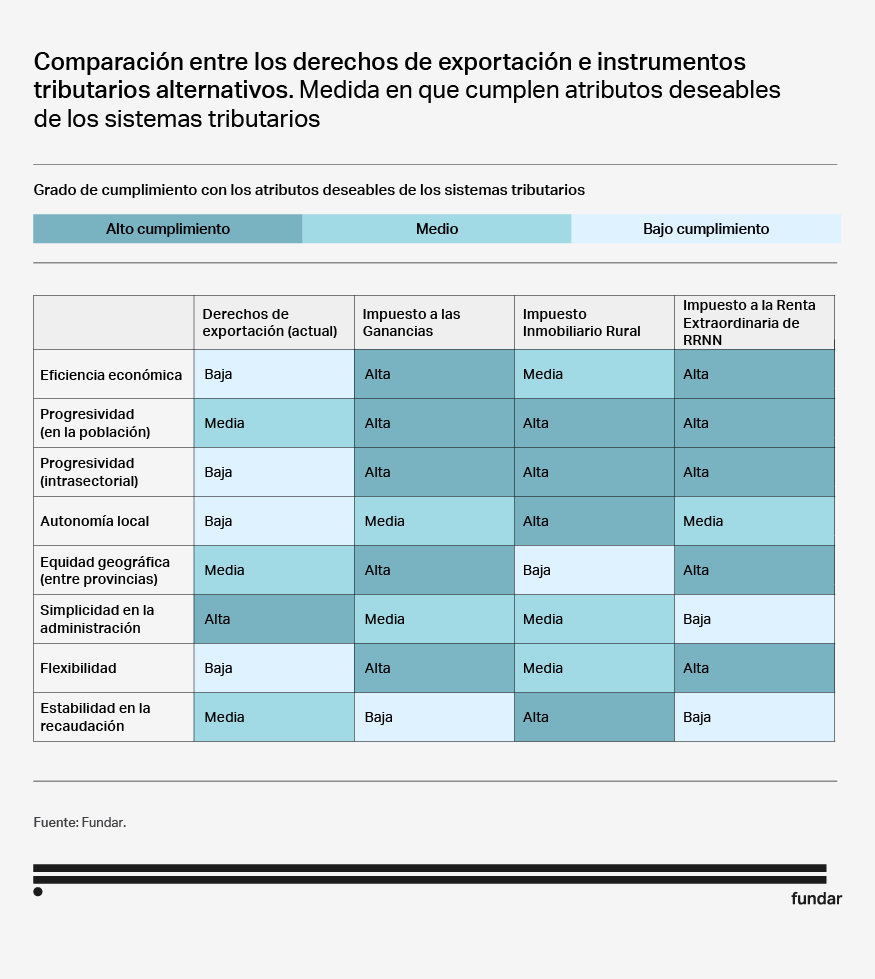

Let us recapitulate: agricultural withholding taxes have great revenue-raising power, an ambivalent distributive effect and a negative effect on production. Taking into account this diagnosis, what are the public policy alternatives?

The fiscal framework for agricultural activity in Argentina is mainly based on taxes that tax production (which limits the productive potential of the sector), do not consider the cost structure of producers (which generates inequalities within it) and have little capacity to adapt to the economic context.

We propose a reform aimed at eliminating export duties in the medium term and replacing them with a set of fiscal instruments aimed at maintaining the level of collection and, at the same time, allowing better productive performance of the agricultural sector and better distributive results.

How much does it cost to eliminate export duties?

If DEX were eliminated, the State would recover 58.9% of this revenue loss through two indirect effects. The first is derived from the increase in domestic prices of agricultural goods, resulting in higher income received by producers and a higher price paid by consumers of these goods and their derivatives. The second effect derives from the increase in agricultural production, stimulated by the tax relief.

However, this recovery is not total, nor is it distributed neutrally among levels of government. With the gradual reduction of export duties, the national government loses tax revenues. This loss (in dark grey) is relatively small in the first year and increases progressively, reaching 0.9% in the fourth year.

The flip side of this loss of tax revenues for the national government is a gain for the provinces (light grey), derived from the increase in the co-participable mass due to the broadening of the tax bases of national co-participable taxes and local taxes.

What are the public policy alternatives?

A reduction in export duties should lead to an automatic (although not necessarily immediate) expansion of the tax base of other taxes, given that new surpluses are generated and an increase in the production of the exempted goods is expected.

However, as we have seen, this automatic recovery is not enough to compensate the totality of the collection loss for the national State. For this purpose, it is necessary to strengthen the collection of other taxes.

Thus, we propose to replace export duties, which are levied on gross sales values, with a strengthening in the collection of taxes levied on net income and property: Income Tax, Rural Real Estate Tax, Personal Property and a Tax on the Extraordinary Income from natural resources.

This mixed system, which combines taxes on fixed assets (Rural Real Estate) and net income (Profits) would have clear advantages over the current system from the point of view of economic efficiency, intra-sector equity and adaptation to the economic context.

At the same time, reducing export duties appears as a precondition to strengthen these alternative taxes aimed at taxing land and agricultural income, since adding fiscal pressure on the sector without first modifying withholdings could be counterproductive in productive terms.

How to promote productive diversification and value addition?

Export duties are also intended to promote productive diversification and value addition through differential taxation between crops and between products with different degrees of processing. In the absence of state intervention, the advantages of soybean cultivation (higher international prices, less need for fertilizers and little organic matter generation in the post-harvest stage), generate incentives to monoculture despite its negative consequences. We propose to maintain a residual rate for soybeans to ensure a differential with corn and encourage crop rotation.

In addition to ensuring a differential in export duties between crops, we suggest maintaining the differential between products with different degrees of processing within the oilseed complex, to encourage the processing of soybeans and sustain the diversification that has been achieved within the complex.

We also propose the creation of a development fund aimed at financing investments in agricultural research and development and the provision of general goods and services, such as rural infrastructure and plant health, to increase sectoral productivity. This type of support is the most efficient for adding value to the agricultural sector.

What would be the consequences for the relationship between the nation and the provinces?

Fiscal reform for the agricultural sector requires not only an adequate technical calibration of the instruments but also multilevel fiscal agreements that establish new arrangements on how public revenues and expenditures are distributed between the Nation and the provinces.

In the current scenario, the National Executive Power has the greatest incentive to sustain agricultural withholdings in the short term: they provide it with a source of tax revenues that are easy to collect and which it does not have to share with the provinces, in a pressing fiscal context. The producing provinces, on the other hand, have strong incentives to advocate for their elimination, since they would benefit from the level of activity and local revenues. The incentives of non-producing provinces depend on the co-participation of export duties.

For this reason, any initiative to reduce export duties should provide for compensation for the main injured party: the national government.

Medium-term, agreement-based change

The timing and form of implementation of these measures is as important as their content. The fiscal needs of the national government in the short term make it inadvisable to implement an immediate reduction of withholding taxes, especially if there is a new devaluation. At the same time, the gradual nature of the reforms provides room for the necessary adjustments to be made and for the actors to adapt to the new regulatory framework.

An act of Congress would be the best way to comply with constitutional provisions, provide predictability to private investment and provide the institutional framework for agreements between the Nation and the provinces.